When the public is polled regarding suburban and urban wildlife, tree squirrels generally rank first as problem makers. Residents complain about them nesting in homes and exploiting bird feeders. Interestingly, squirrels almost always rank first among preferred urban/suburban wildlife species. Such is the paradox they present: We want them and we don’t want them, depending on what they are doing at any given moment.

Although tree squirrels spend a considerable amount of time on the ground, unlike the related ground squirrels, they are more at home in trees. Washington is home to four species of native tree squirrels and two species of introduced tree squirrels. Home ranges for tree squirrels are ½ acre to 10 acres. For the Eastern gray and Eastern fox squirrels living in city parks and suburban yards, home ranges average half an acre.

Facts about Washington tree squirrels

Food and Feeding Habits

- Tree squirrels feed mostly on plant material, including seeds, nuts, acorns, tree buds, berries, leaves, and twigs. However, they are opportunists and also eat fungi, insects, and occasionally birds’ eggs and nestlings.

- Squirrels store food and recover it as needed. Hollow trees, stumps, and abandoned animal burrows are used as storage sites; flowerpots, exhaust pipes, and abandoned cars are also used.

- Scientists credit flying squirrels with helping forest health by spreading species of fungi that help trees grow.

Nest Sites

- Tree squirrels construct nursery nests in hollow trees, abandoned woodpecker cavities, and similar hollows. Where these are unavailable, they will build spherical or cup-shaped nests in trees, attics, and nest boxes.

- An alternate nest may be constructed in a tree for summer use. In areas with prolonged periods of cold weather, red squirrels may construct a winter nest underground, often in or near a food storage site.

- In urban areas, squirrels mostly nest in buildings and other structures.

- Nests contain leaves, twigs, shredded bark, mosses, insulation, and other soft material

Reproduction

- Depending on the species, tree squirrels mate from early winter to late spring. One litter of two to four young is produced from March to June.

- All except flying and western gray squirrels may produce second litters in August or September.

- At about 30 days of age, the young are fully furred and make short trips out of the nest. At about 60 days of age, they begin eating solid foods and venture to the ground.

- At about three months of age, juvenile squirrels are on their own, sometimes remaining close to the nest until their parent’s next breeding period.

- The second litter may stay with the mother in the nest through the winter until well after the winter courtship season.

Mortality and Longevity

- In trees, squirrels are relatively safe, except for an occasional owl or goshawk.

- On the ground, large hawks and owls, domestic cats and dogs, coyotes, and bobcats catch squirrels.

- Vehicles, disease, and starvation also kill squirrels.

- Most squirrels die during their first year; if they survive that, they live three to five years

Common tree squirrels of Washington

Native Washington Tree Squirrel

The Douglas squirrel, or chickaree (Tamiasciurus douglasii)(Fig. 2) measures 10 to 14 inches in length, including its tail. Its upper parts are reddish-or brownish-gray, and its underparts are orange to yellowish. The Douglas squirrel is found in stands of fir, pine, cedar, and other conifers in the Cascade Mountains and western parts of Washington.

The Red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) is about the same size as the Douglas squirrel and lives in coniferous forests and semi-open woods in northeast Washington. It is rusty-red on the upper part and white or grayish white on its underside.

The Western gray squirrel (Sciurus griseus)(Fig. 1) is the largest tree squirrel in Washington, ranging from 18 to 24 inches in length. It has gray upper parts, a creamy undercoat, and its tail is long and bushy with white edges. This species is found in low-elevation oak and conifer woods in parts of western and central Washington.

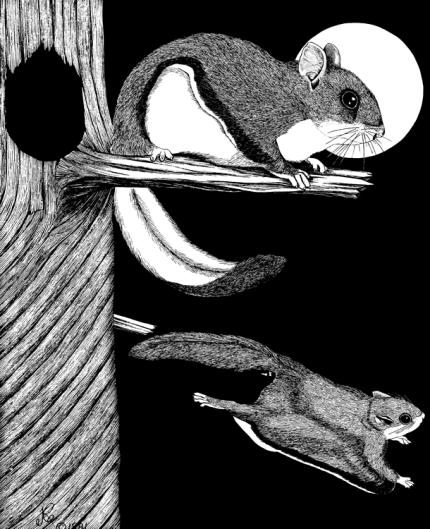

The Northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus)(Fig. 4) is the smallest tree squirrel in Washington, measuring 10 to 12 inches in total length. It is rich brown or dark gray above and creamy below. Its eyes are dark and large, and its tail is wide and flat. These nocturnal gliders are surprisingly common, yet are seldom seen in their forest homes throughout the state.

Introduced Tree Squirrels

The Eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis)(Fig. 3) and Eastern fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) were introduced in Washington in the early 1900s. Since then they have been repeatedly released in parks, campuses, estates, and residential areas. They are now the most common tree squirrels in urban areas.

The upper parts of the Eastern gray squirrel are gray with a reddish wash in summer; its underparts are whitish. It’s about 20 inches long, half of which is its prominent, bushy tail.

The Eastern fox squirrel measures 22 inches in length, including a 9 to 10 inch tail. Its upper parts are usually dark grayish with a reddish cast, and the underparts are orange to deep buff.

The fur color of these two introduced squirrels can vary greatly. Some individuals, even whole populations, may be almost entirely black.

The increasing number of introduced Eastern gray squirrels is often said to be responsible for the decrease in Douglas squirrels in certain areas. However, given that these squirrels have different food and shelter preferences, it’s likely that increasing housing and other development, and loss of coniferous forests is responsible for any decline in Douglas squirrel populations.

Viewing tree squirrels

Tree squirrels have many fascinating behaviors, and—except for nocturnal flying squirrels—they are commonly seen. Tree squirrels don’t hibernate, but will remain in their nests in cold or stormy weather, venturing out to find food they stored nearby.

Squirrels are most active at dawn and dusk, but sharp eyes aided by a pair of binoculars can spot them moving among the treetops any hour of the day. On hot days, squirrels are less active and remain motionless on branches to enjoy whatever breeze is available.

Flying squirrels can go at least three miles in four hours, soaring from tree to tree. Males are particularly prone to traveling, visiting different females in the spring. As proficient as they are in the air, flying squirrels are awkward on the ground. The large flaps of skin that make gliding possible obstruct walking.

Feeding Activity

In the fall, when Douglas squirrels and red squirrels are actively harvesting and storing food for winter, look for “cuttings” under oak, maple, walnut, hazelnut, and coniferous trees. Cuttings are made because seeds and nuts grow in clusters at the end of fragile, easily broken twigs, and squirrels have found that the easiest way to harvest them is to nip these twigs off the parent branch. The squirrels then climb to the ground, harvest the meal, or carry it off to a storage site.

A large pile of cone scales under a tree, called a “midden,” generally indicates Douglas or red squirrels. In winter, holes in the snow may indicate where squirrels retrieved stored food.

Nest Sites

Winter is the time to spot the large, spherical nests built in deciduous trees. Nests are located 15 to 50 feet high, and situated close to the trunk or a main branch.

Tracks and Scratch Marks

In urban areas, squirrels travel via rooftops and power lines, lawns, and concrete, leaving no visible trail. Tracks are also seldom visible on the soft forest floor. However in soft snow, the track pattern of a scampering squirrel can be seen as it leads from tree to tree. If you find tracks starting from an open area in the snow, a flying squirrel may have landed and scampered off.

The hind legs of squirrels are double jointed to help them run up and down trees and other objects. Their front claws are extremely sharp and help in gripping while climbing and traversing. Scratches may be found where squirrels access buildings via downspouts and painted surfaces. Look closely for ¼- to ½-inch long scratches in the paint that appear to have been made by a pin.

Droppings

Tree squirrel droppings are rarely obvious. Areas under a feeder or a nest are good places to check. Droppings are segmented, roughly cylindrical, and ¼ to ½ inch long, with a smooth surface. Coloration is typically black, but can be brown to red.

Calls

The red squirrel and the Douglas squirrel will announce an intruder’s presence with much intensity. This territorial call sounds something like a rapid "tsik tsik tsik, chrrrrrrrr—siew siew siew siew". The call of the Eastern gray squirrel— "que, que, que, que"— is usually accompanied by flicks of the tail. It makes other calls as well, including a loud, nasal cry.

The call of the relatively silent flying squirrel is a quiet, high-pitched, birdlike tick tick.

Tips for attracting tree squirrels

- Keep as much wooded property in a natural condition as you can.

- Include trees and shrubs that provide seeds, nuts, acorns, cones, and fruits at different times of the year.

- Leave dead or dying trees (snags) alone when possible. These provide nest sites and food-storage sites.

- Leave some tree or shrub prunings on the ground for squirrels to gnaw on during winter.

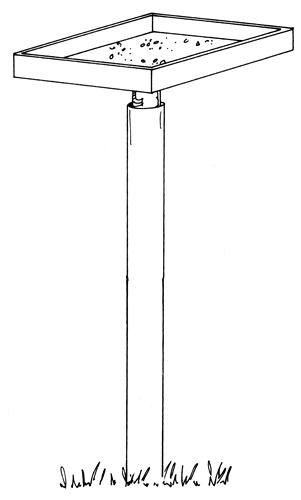

- Install a feeder and a nest box suitable for squirrels or chipmunks (Several flying squirrels will use a duck or owl box for hibernation, and an individual female will use a small box for raising her young.) Be careful when monitoring or cleaning these boxes, because any rodents could carry Hanta virus, which could infect you if dust from dried droppings and urine gets in your eyes, nose, or mouth.

- Keep domestic dogs and cats indoors or fenced.

Preventing conflicts

A tree squirrel’s search for food may bring it to a bird feeder, back door, or a garden containing bulbs. Its search for a nest site may bring it into an attic or down a chimney. The most effective way to prevent conflicts is to modify the habitat around your home so as not to attract squirrels.

To prevent conflicts or remedy existing problems:

Don’t feed squirrels. Tree squirrels that are hand-fed may lose their fear of humans and become aggressive when they don’t get food as expected. These semi-tame squirrels also might approach a neighbor who doesn’t share your appreciation of the animals, which would likely result in them dying.

Eliminate access into buildings. Repair or replace loose or rotting siding, boards, and shingles. When inspecting a building for potential access points, use a tall ladder to view areas in shadows. A pair of low-power (4x) binoculars can be a helpful inspection tool to use before making a dangerous climb. Inspecting the attic or crawl space during the day may reveal light shining through otherwise unnoticed cracks and holes. Native squirrels chew holes 2 inches in diameter; Eastern gray and fox squirrels chew open baseball size holes.

Cover the dryer vent with a commercial vent screen designed to exclude animals without lint clogging. Other vents can be covered with ¼-inch hardware cloth. Some roof-vent caps contain a flimsy, lightweight inner screen that a squirrel can easily penetrate. If the screen has been penetrated, it may be better to replace the whole vent cap with something stronger.

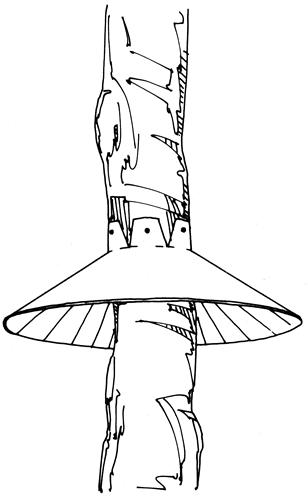

Because squirrels are excellent leapers, keep tree and shrub branches 10 feet away from the sides and tops of buildings. To prevent squirrels from climbing a tree to access a building, install one of the barriers shown in Figure 6. Remove vines that provide squirrels a way to climb structures and hide their access points.

Prevent squirrels from accessing buildings via utility wires by installing 3-foot sections of 2- to 3-inch diameter plastic pipe barriers. Carefully split the pipe lengthwise with a saw, tin snips, or a sharp utility knife, spread the opening apart, and place it over the wire. The pipe will rotate on the wire and the squirrel will tumble off. Do not attempt to install pipe over high-voltage wires. Contact your local electricity/utility company for assistance.

To prevent squirrels from climbing the corner of a building, refer to the figure under "Preventing Conflicts" in Raccoons.

Keep squirrels out of exhaust fans and chimneys (and help them out if they fall in). If a squirrel is trapped down an exhaust fan or a metal lined chimney, you can let the squirrel exit through the house (see "Getting a Squirrel Out of the House") or drop a line down from above so the animal can climb out.

To help the squirrel exit from above, drop down a thick rope or cloth, such as strips of a sheet, so the squirrel can climb out. It is a good idea to tie knots in the rope or cloth 12 inches apart, to provide a secure climbing surface. You may have to tie a couple of lengths together to reach the bottom of the chimney. Tie something to provide weight to the bottom of the rope or cloth, such as a pair of pliers, or other small heavy object.

Lower the rope or cloth slowly, make sure this reaches the bottom, and then secure it at the top. Leave the area completely alone. The squirrel should climb out in 1 to 24 hours.

If the chimney is firebrick then the squirrel can climb out on its own. But if it falls through the flue into the fireplace it usually cannot get back up into the chimney. Open the fireplace door and place a board or branch leading from the fireplace up to the flue. This way the squirrel can climb out on its own. Another option is to prepare the room as described under "Getting a Squirrel Out of the House"

Never leave the squirrel in the chimney or exhaust fan longer than 24 hours—it will die from dehydration. If needed, call a wildlife control company (see Hiring a Wildlife Damage Control Company).

After you are sure no animals are down the chimney, cap it with a commercially engineered chimney cap. Most hardware stores carry these, and chimney cover manufacturers are able to custom fit covers for unusual chimneys.

If a tree squirrel is nesting in a chimney, follow the recommendations given for raccoons under "Raccoons in Dumpsters and Down Chimneys" in Raccoons.

Keep squirrels out of birdhouses. Tree squirrels sometimes raid eggs or small nestlings in nest boxes for food. More often, tree squirrels nest or overwinter in nest boxes intended for native birds.

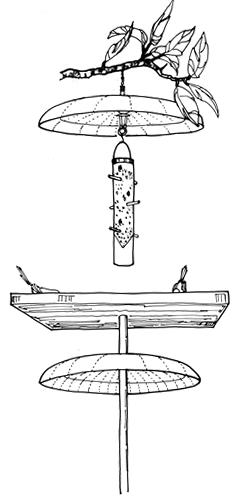

To prevent tree squirrels from climbing up a pole, tree, or other structure supporting a birdhouse, install a barrier (Fig. 5, 6). To prevent squirrels from gnawing around the entry hole of a nest box intended for small birds, attach a pre-drilled metal plate (available from stores catering to the bird-feeding public). Alternatively, attach aluminum flashing or sheet metal to the front of the nest box, and drill an entry hole of the correct size through the flashing. Use a hole-saw bit that cuts through metal and wood, and file down all sharp edges.

Boxes with entry holes large enough to accommodate wood ducks or other large birds should have their entry holes blocked with a rag or other stopper until the desired bird species is seen or heard in the area. Alternatively, nest boxes can be set out with the top (or one of the sides used for cleaning out the box) left open until the desired bird is seen or heard. Immediately after the bird’s nesting season, remove the boxes, or if that is not practical, plug the entrance holes or leave the lids off.

Alternatively, place nest boxes in the most open locations and positions available that will be unattractive to squirrels, but still attract the native birds appropriate to the site.

Keep squirrels out of fruit and nut trees. Install one of the barriers presented and trim lower branches to 5 feet above the ground. Barriers will not work if there are trees, fences, or buildings within 10 feet because squirrels will leap from such objects to reach the food source.

Protect garden bulbs, plants, and seeds. Newly seeded areas and seedlings can be covered with a temporary wire cage or netting made from 1-inch mesh chicken wire. Where bulbs are being dug up, chicken wire can be laid down, securely staked at the edges, and lightly mulched to cover the wire for appearance sake. Commercial taste repellents that prevent squirrels from eating plant material are available from nurseries and hardware stores.

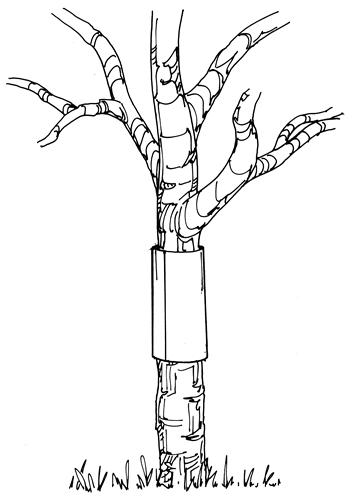

Protect tree bark from being stripped or eaten. Tree squirrels strip the bark off redwood, red cedar, and certain other trees to line their nests. They seek the tender cambium layer of other trees for food. Protect individual trees by installing a barrier (Fig. 7, 8), or by loosely wrapping vulnerable areas with 1-inch chicken wire.

Pepper spray or a commercial taste repellent such as Ropell® can be applied to the bark to prevent bark removal. Applications will need to be repeated in damp weather.

Tree Squirrels in the Attic

The most serious problem with tree squirrels occurs when an adult female squirrel enters an attic or similar space to nest. You may choose to let a squirrel stay if it isn’t posing a problem. However, squirrels gather insulation for nests, create noise (especially on stormy days or nights when squirrels are less likely to be out for food), and may chew electrical wiring, causing electrical problems or fires.

Should you choose to remove the squirrel, a wildlife damage control company can be hired (see Hiring a Wildlife Damage Control Company). You can also do the work yourself by following the steps listed under Evicting Animals from Buildings.

Because attics can be difficult to access and maneuvering around in them can be dangerous, it is recommended that a professional be hired when attics are involved.

If a squirrel has spent a prolonged amount of time in an area with exposed wiring, check your smoke detectors to make sure they are functioning in case of a fire. Also, inspect the area for wire damage or have an electrician inspect it.

Lethal Control

Trapping squirrels should be a last resort, and lethal control can never be justified without a serious effort to apply the above-described preventative control. Killing tree squirrels is also, at best, a short-term solution to any problem you may have. As long as you provide food or shelter and additional squirrels are in the area, other squirrels will move in to replace the ones that you have removed.

Shooting tree squirrels may be helpful if a small, localized population of introduced species is problematic. For safety considerations, shooting is generally limited to rural situations and is considered too hazardous in more populated areas, even if legal.

Don’t trap a problem squirrel in a live trap, thinking that you can release it in another location. Doing so may be illegal (see "Legal Status"). In addition, once in the new location, the squirrel will likely die from hunger, stress, or territorial disputes with other squirrels. Relocated animals can also spread diseases to other squirrels. If they do survive, they are likely to create the same problems in their new home that they created in yours. Finally, in most cases if an area is optimum for squirrels—be it a city park or a wild area—chances are that enough squirrels already live there. One or more of the squirrels is going to have to move or die.

For additional information, see Trapping Wildlife.

Public Health Concerns

Tree squirrels might carry diseases that could affect humans, but, as a practical matter, instances where squirrels have transmitted disease to humans are rare.

You may see a tree squirrel engaging in unusual behavior, such as repeatedly falling over or circling a small area. Such behavior can result from an injury, poisoning, or inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) caused by a parasite.

If a person is bitten or scratched by a tree squirrel, immediately scrub the wound with soap and water. Flush the wound liberally with tap water. Tree squirrels can carry tularemia (see "Public Health Concerns" in Beavers).

In other parts of the United States squirrels can carry rabies. Contact your physician and the local health department immediately. If your pet is bitten, follow the same cleansing procedure and contact your veterinarian. If you can place a large bucket over the squirrel and secure the bucket with a heavy object, the animal can then be held for inspection by a health official.

Legal Status

Because legal status, trapping restrictions, and other information about squirrels change, contact your WDFW Regional Office for updates.

The Western gray squirrel is classified as a threatened species and cannot be hunted, trapped, or killed (WAC 232-12-007). The red squirrel, Douglas squirrel, and Northern flying squirrel are protected species and can be trapped or killed only in emergency situations when they are damaging crops or domestic animals (RCW 77.36.030). A special permit is required in such situations.

The Eastern gray squirrel and Eastern fox squirrel are unclassified and may be trapped or killed year-round as long as you have a hunting license. In such cases, no special trapping permit is necessary for the use of live traps. However, a special trapping permit is required for the use of all traps other than live traps (RCW 77.15.192, 77.15.194; WAC 232-12-142).

It is unlawful to release a squirrel anywhere within the state, other than on the property where it was legally trapped, without a permit to do so (RCW 77.15.250; WAC 232-12-271).

Additional Information

Books

Christensen, James R., and Earl J. Larrison. Mammals of the Pacific Northwest: A Pictorial Introduction. Moscow, ID: University of Idaho Press, 1982.

Hygnstrom, Scott E., et al. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 1994. (Available from: University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension, 202 Natural Resources Hall, Lincoln, NE 68583-0819; phone: 402-472-2188; also see Internet Sites below.)

Ingles, L. G. Mammals of the Pacific States. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1965.

Larrison, Earl J. Mammals of the Northwest: Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and British Columbia. Seattle: Seattle Audubon Society, 1976.

Link, Russell. Landscaping for Wildlife in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 1999.

Maser, Chris. Mammals of the Pacific Northwest: From the Coast to the High Cascades. Corvalis: Oregon State University Press, 1998.

Verts, B. J., and Leslie N. Carraway. Land Mammals of Oregon. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998.