Moderate-

High

The population size of greater sage-grouse in Washington is low. This species requires large landscapes of sagebrush steppe, much of which has been degraded, fragmented, or lost. The primary threat is the combined impact of habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation.

The greater sage-grouse Columbia Basin Distinct Population Segment (DPS) was a candidate for listing under the U. S. Endangered Species Act from 2001-2015. In 2001, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) found that listing of the greater sage-grouse Distinct Population Segment under the Endangered Species Act was "warranted but precluded" by higher priority listing actions. In September 2015, the USFWS decided that the population in Washington did not meet the criteria for a DPS, and listing of the greater sage-grouse across its entire range was not warranted.

Description and Range

Physical description

The greater sage-grouse is the largest North American grouse species. In the breeding season, adult males weigh between 5.5 to 7 pounds, while adult females weigh between 2.9 to 3.7 pounds.

Ecology and life history

Greater sage-grouse require large areas of shrubsteppe habitat dominated by sagebrush. Some degraded habitat that lacks the grass and forb understory needed for nesting and brood rearing is nonetheless suitable for wintering grouse. Greater sage-grouse will also use edges of wheat and alfalfa fields near shrubsteppe habitat.

Sagebrush, grasses, “forbs” (non-woody flowering plants), and insects comprise the annual diet of sage grouse. During the winter, greater sage grouse feed almost exclusively on sagebrush. At other times they also feed on forbs. Sagebrush comprises 60 to 80 percent of the yearly diet of adult sage-grouse and up to 95 to 100 percent of the winter diet. They also eat insects, including ants and grasshoppers, which are essential in the diet of growing chicks. Forbs are important to nesting hens in the pre-laying period and insects are essential for growing chicks.

In the spring, male sage-grouse establish small territories on a lek -- an assembly area where they perform a strutting display to proclaim and defend that territory and attract females. Females incubate a clutch of 6 to 9 eggs in a nest on the ground. Annual adult survival averages 50 to 75 percent, and females may live 8 years or more. Watch greater sage-grouse in the wild in this short video: "Thunder Feathers".

Productive breeding habitat is sagebrush steppe with a diverse herbaceous understory, and springs or wet areas that retain green vegetation in late summer for rearing of growing chicks. Male and female greater sage-grouse gather into flocks in winter, as do hens without broods in early summer. This species generally moves between winter and summer ranges, returning to traditional lek sites in February. Nest predation rates are affected by habitat quality, because grasses help conceal nests.

Geographic range

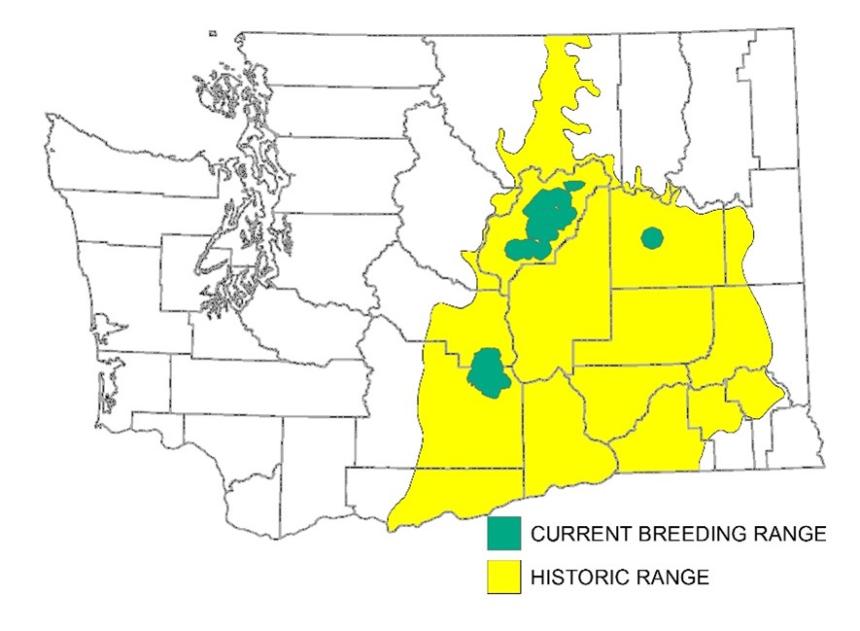

Historically, greater sage-grouse were distributed throughout much of the western United States in 13 states and along the southern border of three western Canadian provinces. In Washington, the range of greater sage grouse once covered half of the land east of the Cascade Mountains. The species have declined dramatically in both distribution and population size in Washington due to conversion to agriculture or other uses.

The current range of sage-grouse is about 8 percent of the historic range, with the grouse occurring in two relatively isolated areas: one primarily on the Yakima Training Center in south-central Washington and the other centered in the Moses Coulee area of Douglas County in north-central Washington. A small reintroduced population also exists in Lincoln County in 2021, but a recent harsh winter and fires in 2020 may result in extinction of that population. The overall population was estimated to be 744 in 2016, but dropped to 676 in 2019. The estimated population then rose to 775 for 2020, but dropped to 699 for 2021. While this indicates that about 90% of grouse survived the 2020 fires and following winter, the impact of the fires on nesting habitat is expected to result in continued declines in the population.

The map shows estimated historic and current range of greater sage-grouse in Washington prior to translocation efforts. For maps of worldwide distribution and other species' information, check out the International Union for Conservation of Nature - Red List and NatureServe Explorer.

Climate vulnerability

Sensitivity to climate change

Moderate-

High

Greater sage-grouse may exhibit some physiological sensitivity to drought conditions, which could result in decreased nest success and/or reduced chick survival. However, their overall sensitivity will be higher due to habitat and foraging requirements. Changes that reduce the availability and quality of sagebrush habitat (e.g., increased temperatures, drought and/or moisture stress, altered fire regimes), which sage-grouse depend on for forage, nesting, and brood-rearing, will adversely impact this species.

Exposure to climate change

Moderate

- Drought and/or moisture stress

- Increased temperatures

- Altered fire regimes

Conservation

Conservation Threats and Actions Needed

- Agriculture and aquaculture side effects

- Threat: Habitat converted to cropland.

- Action Needed: Protect and restore key habitats using a variety of conservation tools; U.S. Department of Agriculture Conservation Reserve Program - State Acres For Wildlife Enhancement (CRP-SAFE) contracts.

- Threat: Wire fences pose collision hazard.

- Action Needed: Attach markers to improve visibility to fences in breeding habitat.

- Fish and wildlife habitat loss or degradation

- Threat: Wildfire impacts to sagebrush.

- Action Needed: Wildfire prevention; sagebrush replanting.

- Threat: Small populations, potential declining genetic health.

- Action Needed: Population introductions, augmentations; more quality habitat.

See the Climate vulnerability section for information about the threats posed by climate change to this species.

In 2020, devastating wildfires burned tens of thousands of acres of eastern Washington sage-grouse habitat. Habitat loss is the single greatest threat to this species and is exacerbated by the immediate threat of wildfire. Full impacts to grouse populations may not not be known for 2 to 3 years, but WDFW estimates that recent wildfires may eventually reduce the number of greater sage-grouse by 30 to 70 percent, bringing the statewide population dangerously low. Surviving birds are more vulnerable to predators and winter conditions.

Our Conservation Efforts

This species was state listed as threatened in 1998, and a state recovery plan was completed in 2004. Declining populations and distribution have resulted in serious concerns for the long-term conservation status of this species. Governmental agencies and nongovernmental organizations are attempting to restore populations of sage-grouse with the aid of land acquisition, habitat improvement, conservation programs, and translocations. Between 2004 and 2016, WDFW, Yakima Training Center, Yakama Nation, and others collaborated to translocate this species from other states (Nevada, Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming) to augment existing populations in Washington.

Resources

References

Stinson, D. W., D. W. Hays, and M. A. Schroeder. 2004. Washington State recovery plan for the greater sage-grouse. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia, Washington.

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2001. 12-month finding for a petition to list the Washington population of western sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus phaios). Federal Register 66:22984-22994.

WDFW publications

PHS Program

Recovery plans

- Recovery of Greater Sage-grouse in Washington: 2023 Progress Report (PDF)

- Recovery of Greater Sage-grouse in Washington: 2019 Progress Report

- Recovery of Greater Sage-grouse in Washington: 2016 Progress Report

- Re-introduction of Sage-grouse to Lincoln County, Washington: 2014 Progress Report

- Re-introduction of Sage-grouse to Lincoln County, Washington: 2013 Progress Report

- Re-introduction of Sage-grouse to Lincoln County, Washington: 2012 Progress Report

- Re-introduction of Sage-grouse to Lincoln County, Washington: 2011 Progress Report

- Re-introduction of Sage-grouse to Lincoln County, Washington: 2010 Progress Report

- Re-introduction of Sage-grouse to Lincoln County, Washington: 2009 Progress Report

- Re-introduction of Sage-grouse to Lincoln County, Washington: 2008 Progress Report

- Greater Sage-grouse Comprehensive Conservation Strategy (2006)

Status reports

- Periodic Status Review for the Greater Sage-grouse in Washington (Apr 2021)

- Washington State Status Report for the Sage Grouse (1998)

- Washington State Recovery Plan for the Greater Sage-Grouse (2004)