Chukars are native to Asia and southern Europe, and they thrive in dry, rocky, steep country, with an emphasis on steep. Although now found through the western United State and in parts of British Columbia and Mexico, some of the best chukar hunting is found in the Snake River region of Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

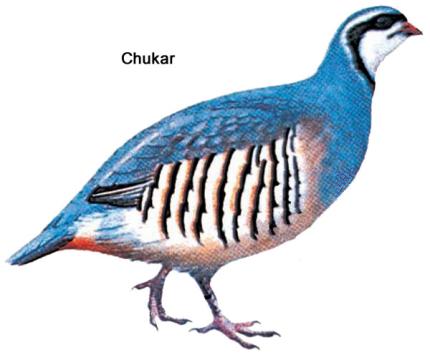

An adult chukar measures 13 to 14 inches long and weighs about three-quarters of pound, a little larger than a valley quail and a little smaller than a ruffed grouse. Also known as red-legged partridge and rock partridge, they’re bluish-gray on the back, wings and breast, with a buff belly and flanks marked with vertical bars of black and chestnut. A black band extends across the eyes and down the side of the head, neck and upper breast. The throat is white, the beak, legs and feet red.

Typical chukar habitat features cliffs, bluffs, canyon walls, talus slopes and other generally vertical real estate. They not only roost in steep, rocky areas, but feed on grains, seeds, forbs and grasses they find among and around the rock piles and cliffs. Brush provides nesting cover in spring and shade from the summer heat, so sage, greasewood and other busy vegetation is also an important part of their habitat. Although they don’t require as much water as other upland bird species, there’s usually a water source of some kind fairly close to where chukars congregate.

Hunting Strategies

Red-legs will sometimes move down to flatter ground to feed at the edge of wheat or hay fields, but chukar hunting is usually a matter of hiking, climbing and crawling up and down steep slopes, around the edges of rock outcroppings and canyon walls. The cooler nights that tend to coincide with the early October partridge season opener may prompt chukars to roost on the warmer south-facing slopes, so these may be the places to explore first thing in the morning. Chukars often feed throughout the morning and then move to shady slopes and draws, dusting sites and water holes during mid-day. They’ll usually begin moving back toward steeper roosting areas late in the afternoon.

Later in the fall, as snow begins to accumulate in Eastern Washington’s chukar haunts, red-legs tend to congregate in areas that are relatively free of snow. Pursuing these birds over snow and ice-covered rocks on their home turf can be risky, but also productive.

While legging it out all day and flushing coveys wherever you find them is standard chukar-hunting procedure, there are other ways to find birds. One is to scan distant slopes with binoculars, looking for feeding or roosting birds, then getting into position for a stalk.

Listening for the clucks and cackles that give the chukar its name is another way to locate birds. Like quail, they call to help maintain contact among members of a covey, and attentive hunters can use those sounds to pinpoint the whereabouts of birds. You can also use a chukar call to draw a response and get the conversation started.

Whenever possible, approach chukars from above. While they tend to fly downhill, they usually run uphill, and they’re about as likely to run as they are to fly, whether approached by a dog or a hunter. Red-legs are notorious for running out of shooting range before rising, and they can get up a hillside much faster than you can. Chasing a covey of runners up the side of a mountain rarely produces a good shooting opportunity.

Something else to keep in mind is the rather high probability that at any given time of day most birds will be at the same approximate elevation, so if you flush a covey at one point along a hillside, move uphill a little and continue along that line in hopes being just above the next covey you encounter.

Chukars have a reputation as spooky birds that don’t hold well for a dog, but, as in any upland bird hunting, a good dog is going to find chukars that even the best two-legged hunter won’t find. A close-working pointer is a good choice as a chukar dog, but a pointer or flusher trained to work below birds and flush them back up toward you is even better. Remember, though, that the steep hills and cliffs that comprise chukar country pose a serious thread to undisciplined or unmanageable dogs.

If you don’t have a bird dog or choose to hunt without one, you can still take chukars. One tactic is to spot, stalk and rush a covey. Another is to do a stop-and-go push through likely looking chukar spots, moving quickly while walking, then stopping for 30 seconds near cover to make hiding birds loose their nerve and flush.

Guns and Ammunition

Both 20-gauge and 12-gauge guns are good choices for chukar hunting, 20’s because they’re smaller and lighter and 12’s because a bigger 12-gauge load means more shot in the pattern when you’re trying to hit a bird that flies fast and may change direction in an instant. Chukars don’t hold as tightly as some other birds, so more shots tend to be in the 30- to 40-yard range, or longer. Many chukar hunters like a modified choke or, if they shoot a double-barrel, a modified/full or improved/full combination.

Sling-equipped shotguns aren’t too common outside waterfowl-hunting circles, but a chukar hunter might consider that option. A shoulder sling can come in handy while climbing around the kind of terrain that these birds inhabit.

Like quail and gray partridge, it doesn’t take a heavy load of large shot to bring down a chukar. The more shot in the load, though, the better the chances that a few will find their mark. On the other hand, longer shots are the norm with chukars, so a hunter has to weigh the advantage of more small shot against the added knock-down power at greater distance of larger shot. A good compromise might be a 1 ¼-ounce load of size 7 ½ shot (in a 3-inch 20-gauge or 2 ¾-inch 12-gauge shell) for a first shot, followed by a similar-sized load of 6’s for a second.

Shooting

When flushed, chukars usually fly downhill, so unlike other upland birds, they’re dropping, not rising, when you shoot at them. Old habits die hard, especially in shooting, so if you’re used to shooting pheasant, quail and grouse, you’re very likely to shoot over your first several chukars. And it’s difficult to practice on dropping shots at a trap range or sporting clays course because by the time a clay bird from a trap starts to drop, it’s often out of range. One option is to find a place where you can shoot downhill and have someone throw clay birds for you by hand or with a hand-thrower. When you’re shooting at the real thing, though, the best advice is to take a little more time with your shot, swinging on the bird an additional second or two to get the hang of downhill shooting.