ARCHIVED NEWS RELEASE

This document is provided for archival purposes only. Archived documents

do not reflect current WDFW regulations or policy and may contain factual

inaccuracies.

News release Aug. 30, 2019

Abby Tobin, White-nose Syndrome Coordinator (WDFW), 360-999-7958

Rachel Blomker, Communications Manager (WDFW), 360-701-3101

David Eisenhauer, Public Affairs Officer (USFWS), 413-253-8492

OLYMPIA – White-nose syndrome, an often-fatal disease of hibernating bats, has been confirmed for the first time in Washington east of the Cascade Range. Kittitas County is the fourth county in Washington affected by the disease or the causal fungus, joining King, Pierce, and Lewis counties.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) received four dead bats from a landowner outside of Cle Elum this spring. WDFW sent the bats to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, WI for testing, where scientists confirmed all four bats had white-nose syndrome. The bat species are either Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis) or little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus), two species that are hard to tell apart visually.

Earlier this year, the same landowner alerted WDFW that a large group of bats has lived on their property for over 50 years. Biologists confirmed it was a maternity colony, which is where female bats give birth and nurse their young. In August, scientists counted more than 750 bats at the site.

“We are thankful that this homeowner was a caring steward of these bats and reached out to let us know about the bats on their property, and for reporting the dead bats,” said Abby Tobin, white-nose syndrome coordinator for WDFW. “We rely on these types of tips from the public of sick or dead bats, or groups of bats, to monitor bat populations and track the spread of this deadly bat disease.”

White-nose syndrome is harmful to hibernating bats, but does not affect humans, livestock, or other wildlife.

In 2016, scientists first documented white-nose syndrome in Washington near North Bend in King County. Since then, WDFW has confirmed 34 cases of the disease in three bat species in the state. A timeline of fungus and white-nose syndrome detections in Washington is available online at https://wdfw.wa.gov/bats.

First seen in North America in 2006 in eastern New York, white-nose syndrome has killed millions of bats in eastern North America and has now spread to 33 states and seven Canadian provinces.

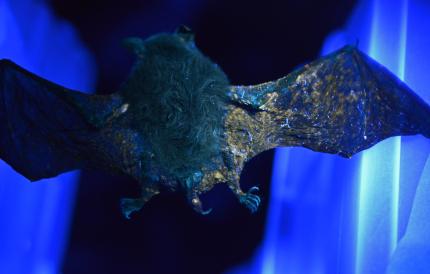

The disease is caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which attacks the skin of hibernating bats and damages their delicate wings, making it difficult to fly. Infected bats often leave too early from hibernation, which causes them to lose their fat reserves and become dehydrated or starve to death.

As predators of night-flying insects, bats play an important ecological role in preserving the natural balance of your property or neighborhood. Washington is home to 15 bat species that benefit humans by eating tons of insects that can negatively affect forest health, commercial crops, and human health and well-being.

WDFW collaborates with partners, including U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington State Department of Health, wildlife rehabilitators, and others to collect samples from bats and the areas where they live around the state for the past three years. This proactive surveillance work helps scientists detect the presence of the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome and track its spread.

WDFW urges people to not handle animals that appear sick or are found dead. If you find sick, dead, or groups of bats, or notice bats acting strangely, such as flying outside during the day or freezing weather, please report your sighting online at https://wdfw.wa.gov/bats or call WDFW at 360-902-2515.

Even though the fungus is primarily spread from bat-to-bat contact, humans can unintentionally spread it as well. People can carry fungal spores on clothing, shoes, or recreation equipment that touches the fungus. This precaution may be particularly important in areas where natural barriers like the Cascade Range may slow the natural movement of the fungus across the landscape.

To learn more about the disease and the national white-nose syndrome response, and to get the most updated decontamination protocols and other guidance documents, visit www.whitenosesyndrome.org.

For more information on Washington bats, visit https://wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/living/species-facts/bats.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is the state agency tasked with preserving, protecting, and perpetuating fish, wildlife, and ecosystems, while providing sustainable fishing, hunting, and other recreation opportunities.