Since the 1970s, federal agencies have worked closely with states and treaty tribes in the Pacific Northwest to reverse the decline of native salmon populations. As partners in this effort, they have restructured fisheries, updated hatchery practices, and allocated funding to restore wild, naturally spawning stocks listed for protection under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA).

The state of Washington has the largest system of salmon hatcheries in the world, raising more than 200 million juvenile fish at more than 100 state, federal, and tribal facilities each year. These hatcheries produce the majority of all salmon caught in Washington waters, contributing to the statewide economy. According to one economic analysis, the state operated hatcheries alone generate nearly $70 million in personal income from fishing each year.

Mass-marking has played a vital role in salmon management since the mid-1990s, when concerns about the decline of wild salmon populations became increasingly acute. In response, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) launched a pioneering effort to visibly mark hatchery-raised salmon so they can be readily distinguished from wild fish in Northwest waters.

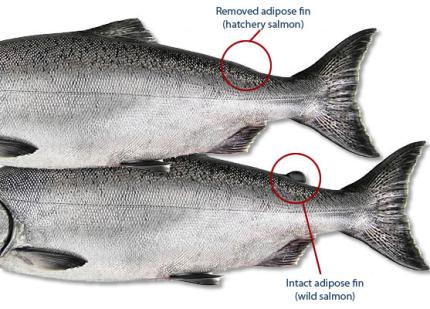

Today, virtually all coho and Chinook salmon produced in Washington hatcheries -- including those raised in federal and tribal facilities -- are mass-marked by clipping the small adipose fin near their tail. This strategy has revolutionized salmon management and provided an indispensable tool in the broad-based effort to recover wild salmon stocks throughout the region.

Prior to mass-marking, restrictions imposed by new ESA listings threatened to close or greatly curtail historic salmon fisheries throughout the region. In addition to the recreational and cultural values involved, the potential loss of fishing opportunities presented a severe economic threat to fishing families and entire communities, especially in rural areas of the Northwest.

Once mass-marking was established, fishery managers were able to mitigate that situation by creating a growing number of "mark-selective fisheries," which require fishers to release any unmarked -- presumably wild -- salmon or steelhead they encounter. These rules protect wild salmon, while permitting fishers to retain hatchery fish produced for harvest.

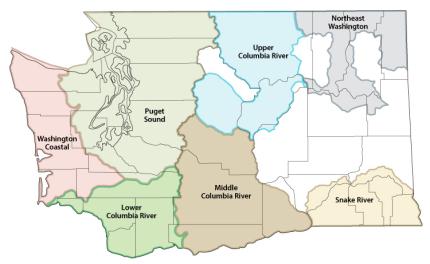

WDFW employs mark-selective rules in recreational fisheries throughout the state, and is expanding their application in commercial fisheries on the Columbia River under a broad-based reform measure jointly approved by Oregon early this year. The impacts of these fisheries are closely monitored and subject to strict federal limits.

Mass-marking and salmon recovery

Equally important is the contribution mass-marking has made to the state's ongoing salmon recovery effort. Several key recovery objectives depend on the ability of fish managers, scientists and technicians to identify hatchery fish on sight:

- Population assessments: Accurate assessment of the number of wild vs. hatchery fish is essential in efforts to recover wild salmon populations. In recent years, fishery managers discovered that they had long overestimated the number of wild salmon returning to Washington's rivers and streams before mass-marking was in effect.

- Broodstock management: NOAA-Fisheries requires that all state and tribal hatcheries include a minimum number of wild fish in their fish-production programs, as specified in Hatchery and Genetic Management Plans for each facility. Mass-marking helps hatchery workers meet those goals by making hatchery fish readily identifiable.

- Limiting strays: Salmon recovery plans in most watersheds establish objectives for limiting the number of hatchery fish that stray into areas used by wild salmon to spawn. Visual identification makes it possible for salmon managers to determine the number of hatchery fish on the spawning grounds and take corrective action.

All of these recovery strategies were included in recommendations by the independent Hatchery Scientific Review Group, appointed by Congress in 2000 to assess the practices of salmon hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest. Today, they also figure prominently in federal recovery plans in effect throughout the state.

Mass-marking has become an integral part of state, federal, and tribal hatchery operations throughout the Pacific Northwest. It has led to the creation of new, sustainable salmon fisheries and provided an invaluable tool in the effort to recover wild salmon populations. Continued federal support is needed for that effort to move forward.