ARCHIVED NEWS RELEASE

This document is provided for archival purposes only. Archived documents

do not reflect current WDFW regulations or policy and may contain factual

inaccuracies.

News release Jan. 7, 2020

Abby Tobin, White-nose Syndrome Coordinator (WDFW), 360-999-7958

Rachel Blomker, Communications Manager (WDFW), 360-701-3101

David Eisenhauer, Public Affairs Officer (USFWS), 413-253-8492

Marisa Lubeck, Public Affairs Specialist (USGS), 303-526-6694

OLYMPIA – White-nose syndrome, an often-fatal disease of hibernating bats, has been confirmed for the first time in a fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes) in King County, Washington. This finding brings the total number of bat species confirmed with the disease in North America to 13.

First seen in North America in 2006 in eastern New York, white-nose syndrome is a fungal disease that has killed millions of hibernating bats in eastern North America and has now spread to 33 states and seven Canadian provinces. The disease does not affect humans, livestock, or other wildlife.

The disease is caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which attacks the skin of hibernating bats and damages their delicate wings, making it difficult to fly. Infected bats often leave hibernation too early, which causes them to burn through their fat reserves and become dehydrated or starve to death.

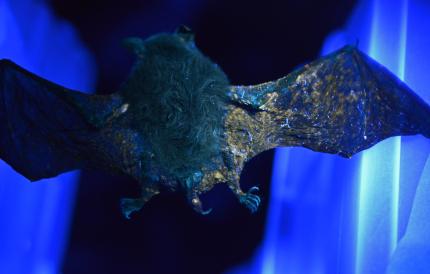

The Cedar River Education Center near North Bend reported a dead bat outside its facility in April 2017. A biologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) retrieved the dead bat and did a field test using Ultraviolet (UV) light to detect the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome. Under UV light, bats with white-nose syndrome usually have an orange glow on their wings.

The bat was later confirmed to have white-nose syndrome by the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. To identify the bat species, the Northern Arizona University’s Bat Ecology and Genetic Lab tested the bat using a genetic method than can identify 92% of the world’s bat species. Although the results did not show a conclusive identification, scientists were able to narrow it down to two closely-related bat species – long-eared myotis and fringed myotis.

“With the possibility of a new bat species affected by white-nose syndrome, we explored ways to confirm the species using additional genetic testing,” said Abby Tobin, white-nose syndrome coordinator for WDFW. “Fortunately, our partners at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, WI stepped up to the challenge.”

Jeff Lorch, a microbiologist at the USGS National Wildlife Health Center, used nuclear DNA testing to confirm the bat as a fringed myotis in December 2019.

“There are two parts of a cell that carry DNA – the nucleus and the mitochondria,” said Lorch. “Most bat genetic testing has used mitochondria DNA, which does not allow us to distinguish the long-eared bat from the fringed bat. By using nuclear DNA, we were able to get more accurate results.”

Fringed bats are widely dispersed in dry forests throughout western North America from Mexico to British Columbia. However, there is a lack of data on the bat’s population size, health trends, or where they hibernate in winter.

“Tracking white-nose syndrome and its effects on bat populations is challenging when little is known about bats in Washington, and this species in particular,” said Tobin. “The confirmation of white-nose syndrome in another bat species is a reminder of how much we still have to learn about this devastating disease.”

In 2016, scientists first documented white-nose syndrome in Washington near North Bend in King County. Since then, WDFW has confirmed 46 cases of the disease and/or the fungus in four bat species in the state. A timeline of fungus and white-nose syndrome detections in Washington is available online at https://wdfw.wa.gov/bats.

WDFW staff urge people to not handle wild animals, and to not touch bats that appear sick or are found dead. Even though the fungus is primarily spread by bats themselves, humans can unintentionally spread it as well. People can carry fungal spores on clothing, shoes, or recreation equipment that touches the fungus.

Those who find sick or dead bats, or notice bats acting strangely, such as flying outside during the day or in freezing weather, can report their sighting online at https://wdfw.wa.gov/bats or call WDFW at 360-902-2515. WDFW also seeks reports of groups of healthy bats.

To learn more about the disease and the national white-nose syndrome response, and to get the most updated decontamination protocols and other guidance documents, visit www.whitenosesyndrome.org.

For more information on Washington bats, visit https://wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/living/species-facts/bats.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is the state agency tasked with preserving, protecting, and perpetuating fish, wildlife, and ecosystems, while providing sustainable fishing, hunting, and other recreation opportunities.