While native to parts of North America, wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) were introduced to Washington beginning in the early twentieth century. Wild turkeys are one of the most charismatic and iconic bird species in North America. An eagerly sought game species, turkeys hold significant cultural value to recreationists and holiday celebrations. Turkeys are recognized as the state game bird for Alabama, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, and South Carolina. Wild turkeys belong to the family Phasianadae within the order Galliformes, the same order that chickens, grouse, and other heavy bodied ground feeding birds belong, often referred to as gallinaceous birds. You can observe turkeys throughout most of eastern Washington and the eastern foothills of the Cascade Mountains. Small populations also occur sparsely in western Washington.

Description and Range

Physical description

Reminiscent of plump, feathered dinosaurs, turkeys are heavy bodied with bald, slender heads, and large feet. With adult males weighing more than 20 pounds, turkeys are the largest game bird in North America and have brown feathers with an iridescent sheen giving way to hues of green and copper.

Male and female turkeys are sexually dimorphic, meaning the sexes are different in appearance and size. Usually, males are larger, heavier, and more colorful than females. You can use beards, which are modified feathers, to determine the age and health of male birds. If a turkey has a longer beard, that indicates it’s an older male in good condition. Some female turkeys (10-20 percent) will also grow a beard, but they are typically smaller and do not correlate as well to age.

Subspecies

There are three subspecies of turkey in Washington - the Merriam’s, Rio Grande, and Eastern turkey. Location and tail feather color can help you differentiate between the different sub-species.

The Merriam’s subspecies occupies portions of Ferry, Stevens, Pend Oreille, Spokane, Okanogan, Chelan, Kittitas, Yakima, Klickitat, and Skamania counties. The tips of the Merriam's tail features are white.

The Rio Grande subspecies can be found in Asotin, Columbia, Garfield, Lincoln, Walla Walla, and Whitman counties. The tips of the Rio Grande's tail features are tan.

The Eastern subspecies can be found west of the Cascades in Cowlitz, Lewis, Thurston, and Wahkiakum counties. The tips of the Eastern's tail features are chestnut brown.

Geographic range

People have tried to introduce wild turkeys in Washington as early as 1913, but efforts didn’t yield sustainable breeding populations until the 1960’s. The most recent introductions occurred in 2003.

Eastern turkeys are the only subspecies present in western Washington, and you can occasionally find them in Lewis, Pierce, and Thurston counties. You can find Merriam’s throughout central Washington and the northeast. Rio Grande turkeys are concentrated in the southeastern corner of the state, but some birds have also hybridized with Merriam’s turkeys in northeastern Washington.

Ideal turkey habitat includes a wide variety of landscape types including mixed tree, shrub, and grass types. However, turkeys also thrive in urban areas.

- Eastern turkey native habitat includes hardwood trees and other mixed forests.

- Merriam’s turkey native habitat includes coniferous mountains and canyon-lands. Areas with evergreens like Ponderosa pine are common.

- Rio Grande turkey native habitat includes grasslands and prairie predominantly, with areas of wooded rangeland.

Regulations

Licenses and permits

Turkey hunters must buy a small game license and turkey transport tag to legally harvest turkeys during the spring and fall seasons. You can buy a small game license in combination with a big game license or on its own. Hunters can also buy a three-day small game license. You can buy licenses at fishhunt.wa.gov.

Youth and disability permits are also available. Youth hunters must be under 16-years-old when they buy a license. For more information about hunting for persons with disabilities, refer to the Big Game or Migratory Waterfowl and Upland Game pamphlets for requirements.

Make sure you have the necessary parking passes for your hunt. To park at recreational properties owned or managed by Washington State Parks or the Washington Department of Natural resources, you will need a Discover Pass. The Discover Pass is also valid on WDFW lands.

Rules and seasons

For information about turkey hunting and seasons, please see our Hunting Regulations website. Spring season information is available in the Wild Turkey Spring Season regulations pamphlet. Fall regulations can be found in the Game Bird pamphlet.

Legal Status

Turkeys are classified as a game species under WAC 220-416-010. You must get a hunting license to legally hunt them during the spring, fall, youth, or special permit seasons.

Permits may be granted to hunt turkey that are damaging personal property (WAC-220-440-200).

It is unlawful to utilize live decoys or bait to hunt turkey pursuant to WAC-220-416-030 and WAC-220-416-100.

Conservation

Living with wildlife

Food and feeding habits

Turkeys congregate where there are ample resources, favoring areas with nuts and fruit. These large birds have an eclectic palate, supplementing their diet with seeds and vegetation, but will even consume invertebrates, small lizards, and amphibians.

As a truly opportunistic forager, turkeys will eat whatever is abundant each season. In spring and summer, turkeys will scratch the ground for seeds, nip at buds, and consume berries or the occasional small animal. In the colder months, they depend on tree nuts and vegetation and will often gather in large flocks.

Nests and nest sites

Turkeys are a ground nesting bird, which requires females, called hens, to be picky about nest sites. To avoid predation, hens choose sites with ample cover like brambles, branches, or other vegetation. While cover is important, hens also select sites where they have good visibility to watch for predators while incubating eggs.

Hens make nests by scratching out a shallow depression about one inch deep with a footlong perimeter. Turkey nests are strategically subtle – hens will line their nest by using materials available at the nest site.

Reproduction

Breeding usually takes place between late February and April each year. Seasonal conditions, like available daylight, may affect the timing and duration of courtship.

Male turkeys, or toms, will mate with several hens during the breeding season.

Over two weeks, hens will lay one egg per day. The number of eggs she lays, called a clutch, ranges from four to 18 eggs. Hens will incubate their eggs from 25-31 days. Hatchlings are precocial, which means chicks can walk and feed themselves within minutes after hatching - though they still need mom to show them where to find food and to protect them from predators. Hens raise their young, also called poults, on their own.

Multiple hens may be seen traveling around with large flocks of poults, or broods, much like chaperones on a school field trip. Merging broods is an adaptation that increases vigilance for predators and helps turkeys forage together where resources are abundant. Poults typically stay with their mother for up to 10 months.

Longevity and mortality

Turkeys face predation at every life stage. Their list of potential predators is extensive, with more than 20 known predators in Washington, including:

- Small carnivores (weasels and rats)

- Mid-sized carnivores (bobcats, skunks, opossums, coyotes, raccoons, foxes)

- Large carnivores (bears, wolves, and cougars)

- Raptors (owls, hawks, and eagles)

- Corvids (crows and ravens)

- Reptiles (primarily snakes)

Viewing wild turkeys

Displays

Spring is the best time to view dynamic turkey behavior. The most recognizable behaviors during breeding season are vocalizations. Gobbling toms can be heard as far as a mile away in good weather.

Toms will puff and strut their stuff to impress hens, fanning their tail feathers and dragging their primary feathers along the ground to show off their plumage. Listen closely during these displays for a low-pitched drumming sound.

When competing for mates, toms will fight one another for the opportunity to breed. Later in the season toms will strut as a sign of dominance where other males are present. Hens will strut occasionally when provoked.

Nest sites

Turkey nests are typically well hidden and difficult to access. Hens will raise their head on the lookout for predators while they sit on eggs. If you see a turkey on the nest, keep your distance to avoid disturbing the hen.

Molting

Like most birds, turkeys undergo annual molts. Poults molt several times before their adult plumage grows in.

Adult turkeys molt in the spring breeding season. Beards do not molt with the feathers but continue to grow over a turkey’s lifetime.

Calls

Although a tom’s gobble is easily the most widely recognized turkey call, the species has a range of vocalizations. Turkeys can cluck, purr, cutt, yelp, and cackle.

- Gobbling – Largely a means to attract females during breeding season.

- Clucking – A hen’s communication to let toms know she is in the area.

- Clucks and purrs – These sounds are heard within a flock, often when the flock is at ease.

- Cutting – An excited call typically made by hens.

- Yelps – Another way for hens to get the attention of toms. An excited yelp is made when a hen is agitated in some way.

- Cackling – This vocalization is heard when birds leave their roost.

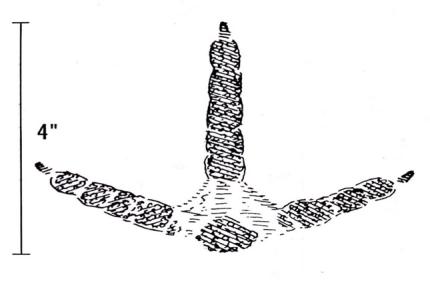

Photo from the Peterson “Animal Tracks” Guide

Tracks

Turkey tracks are quite visible, especially along dusty trails. Easily identified as large chicken feet, their tracks can measure between three and four inches long. On the ground, you’ll see the foot’s three front toes splayed out, and occasionally a faint spot in the back made by the shorter hind toe. Often their tracks form a straight line.

Within the first two weeks after hatching, the average poult mortality rate may be 60 percent or more. The typical lifespan of a wild turkey is about three years - though there are records of birds that have lived as long as 15 years.

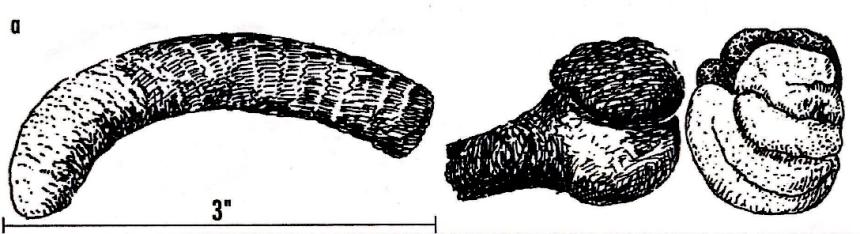

Droppings

Droppings usually come in one of two forms. Most recognized is the tube-shaped pellet, which can end with a hook or “j” shaped tip. Toms typically leave these droppings. Hens tend to produce a rounder dropping with a resemblance to popcorn.

Roost sites

Roosts are a critical resource for turkeys. These sites not only offer protection from predators, but also the harsh weather. Turkeys prefer large, tall trees, where they will roost as high as they can overnight. Turkeys may either roost at the same site or move to a new area each night. Turkeys may also use a house or cluster of trees on private property as a roost, which can result in a conflict situation.

Preventing conflict

The areas where turkeys find suitable habitat often overlap with human resources. Turkeys seek easy, readily available food sources. Some of these human-associated food sources may be agricultural fields, gardens, orchards, and haystacks (particularly hay with seeds in it, e.g. oat hay). Turkeys will typically avoid people, though they may act aggressive towards pets or people when they are fed by humans, habituated to humans, cornered, feel threatened, are sick, injured, or malnourished, defending young or food, or during the mating season. Turkeys are known to peck and damage windows, screens or other objects that cast a reflection. Large flocks may also deposit high volumes of droppings at roost or forage sites, which may coincidentally be a lawn or parking lot. Other behaviors such as vocalizations may pose a disturbance as well.

With most human-wildlife conflict, the best solution to reduce conflict is proactive prevention. You can do these preventative actions consistently throughout the year or on a seasonal basis when conflict risk is high. Allowing turkeys to become comfortable around people creates a challenge to landowners who experience property damage. People should be able to recognize turkey sign and be aware of their surroundings to help prevent conflict. Adults should be present with their pets and children when in the yard and keep them within arm’s reach or keep pets leashed when recreating through turkey habitat.

To prevent conflicts or mitigate existing problems

Changing and adapting human behavior for positive short and long-term gains

The number one thing you can do to mitigate conflict is change human practices and behavior. Landowners should invest and proactively plan to protect high value property and objects from turkeys and other wildlife. They should also be aware that the use of bird feeders may attract turkeys and other wildlife, which often leads to other conflict. Landowners should be prepared if they live in turkey habitat and seek to coexist with turkeys in these areas.

Do not feed turkeys

Not only can supplementing food cause serious health concerns for wildlife, but it can lead to unintended consequences that threaten you, your neighbors, and both human and wildlife communities. In this instance, habituation is the conditioning of a wild animal to humans via feeding or some other positive interaction. A habituated turkey may change the way it uses habitat, where and when it moves, and may not be afraid of people or pets. As wild animals begin to associate humans with safety from predation, environmental pressures, and food, there is an increased likelihood of an interaction with those species. Most of the time these interactions with wild animals are not negative experiences, but it is important to keep wildlife wild to reduce the risk of a negative interaction.

When humans feed turkeys regularly, wild birds can come from miles away to feed as well. With the increased numbers of wild birds in one area, you could inadvertently contribute to disease transfer among turkeys. As turkeys are attracted to an area by supplemental feeding, their predators can then also be attracted to that area. If you are attracting turkeys by feeding them you can expect to also attract any of a turkeys’ predators, large and small.

Habitat modification

Turkeys can adapt to a variety of habitats across rural and urban areas. Modifying habitat to deter turkeys can be difficult. People can plant or preserve a variety of native turkey food on the perimeter of their property to provide short and long-term food supplies for turkeys. These food sources could act as a lure and alternative food source to attract turkeys away from high value crops or gardens. Landowners can also maintain their yards and gardens to be less attractive to turkeys by keeping their grass short, by minimizing the number of mast-producing shrubs and trees, and by removing any roost and cover habitat such as dense vegetation.

Exclusion

You can use weave nets attached to other structures, such as fencing, to keep turkeys out of sensitive or high-risk areas. Bird spikes or ledge exclusion products can deter turkeys from roosting in undesirable places. To protect stored hay, try tarping haystacks or closing off haybarns with fencing to keep birds out.

Changing and adapting turkey behavior for positive short and long-term gains

People should apply consistent and adaptive use of non-malicious hazing techniques to provoke a fear response from turkeys at identified roost sites, and when turkeys are present. You can accomplish this using water, spotlights, and other non-lethal devices. These methods may encourage the turkey to find a different roost location or to use other habitats. Turkeys are attracted to and curious about shiny and reflective objects. Cover these objects to prevent glare or reflections.

Behavior modification through fear-provoking tactics

Frightening devices

Do not physically harm turkeys when you use any frightening or hazing techniques.

You may be able to temporarily deter turkeys by using motion-sensing sprinklers, propane cannons, radios, and scarecrows. Adjust these items every few days, and for best results, use several techniques at a time.

Lasers: Some evidence suggests that turkeys will fly if a red laser is shined in their eye. Take precaution to follow safety guidelines when utilizing lasers.

Pyrotechnics: Fireworks or shotgun blasts (pointed in a safe direction) may also result in a fear response and keep turkeys at bay. You could also consider using a paintball gun. Check your local laws and ordinances before using these tactics.

Dogs: Well-controlled dogs directed by a handler may chase turkeys off private property. Dog owners should be aware of dog-related policies in areas commonly used by the public, such as residential areas and parks.

ATVs: Some landowners have success in patrolling their properties and hazing turkeys using ATVs.

Falconry: Emerging methods in hazing include collaboration with certified falconers. These practices are still being tested in urban and rural settings to gauge public satisfaction and behavior response results. Falconers must follow all applicable regulations.

Chemical repellents

You can protect valuable crops and ornamental plants such as cherries, grapes, and blueberries with products that contain methyl anthranilate. These ingredients can also help to disperse roosting turkeys.

Deterring aggressive turkeys

Wild turkeys maintain a “pecking order” and may try to intimidate humans as they would other turkeys. Make sure you don’t encourage turkeys to be around people.

Practice being bold and don’t hesitate to scare turkeys from private property. Some people find that making loud noise, swatting turkeys with a broom, or spraying them with a hose can deter aggressive birds. Bottom line – don’t let them intimidate you!

Translocation and relocation

It is unlawful to capture and relocate wildlife without a permit issued by the WDFW Director except as otherwise provided by department rule. WDFW staff may trap turkeys for translocation or relocation where appropriate. Wildlife Control Operators (WCOs) are not permitted to trap, translocate or relocate wild turkeys under their certification.

Relocation of turkeys is not a preferred option, as it is likely they will return to the site of conflict. For a translocation to be successful the turkeys need to be relocated at least 15 miles away to an area that is not already at carrying capacity for turkeys and where the likelihood of causing conflict is minimal.

Lethal Control

If the above nonlethal control efforts are unsuccessful over time, and the damage situation persists, lethal control may be an option. Lethal control techniques include legal hunting during the turkey hunting season (hunting seasons and regulations found here) and other actions with a WDFW authorized permit. Turkeys are a game species in Washington. Legal hunts require a small game license and valid turkey transport tag. Hunters looking for public access to private lands may contact a Private Lands Biologist through a WDFW Regional Office, or find more information online to learn about the WDFW Private Lands Program.

A Damage Prevention Cooperative Agreement and recorded use of nonlethal methods are required to receive a Damage Prevention or other permit from WDFW. These permits are required to lethally remove wild turkeys outside of hunting seasons. Contact your local Wildlife Conflict Specialist through a WDFW Regional Office for additional information.

Because wild turkeys are a game bird, landowners should check with a local Wildlife Conflict Specialist to discuss which deterrent methods (non-lethal or lethal) to use on their property.

Public health concerns

Wild turkeys are susceptible to several infectious diseases that may be transmitted to domestic poultry including chickens, turkeys, and other fowl. Although turkeys have yet to be reported as a source of any outbreaks, potential risks should be identified.

Viruses: Avian pox, western equine encephalitis, mycoplasmosis (rare in wild populations, more common in domestic flocks).

Parasites: Histomoniasis (blackhead disease), coccidiosis (intestinal parasite), cestodes (tapeworms), nematodes (roundworm), and trematodes (flukes or flatworms), ticks, feather lice, mites.

Bacteria: Salmonella.

Resources

WDFW Publications

- Morgan, J.T., D. A Ware, M. Tirhi, and R. L. Milner. 2004. Wild Turkey. 18-1 – 18-7 in E. Larsen, J. M. Azerrad, N. Nordstrom, editors. Management Recommendations for Washington’s Priority Species, Volume IV: Birds. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia, Washington, USA.

- WDFW Game Management Plan (2015 - 2021)

- WDFW Wild Turkey Management Plan (2005 - 2010)

Other

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Seattle Audubon’s Birds of Washington State

- National Wild Turkey Federation

- Oates, David W.; Wallner-Pendleton, Eva A.; Kanev, Ivan; Sterner, Mauritz C.; Cerny, Henry E.; Colli. 2005. A survey of infectious diseases and parasites in wild turkeys from Nebraska. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/_/print/PrintArticle.aspx?id=206532009