Muskrats get their common name from their resemblance to stocky rats and from the musky odor produced by their scent glands.

Description and Range

Physical description

Muskrats weigh 2 to 4 pounds and reach lengths of 18 to 25 inches, including their 8- to 11-inch, sparsely haired tails. Their coat color is generally dark brown, but individuals can range from black to almost white. Muskrats have partially webbed hind feet that function as paddles and much smaller front feet used primarily for digging.

Geographic range

Muskrats are found throughout still or slow-moving waterways, including marshes, beaver ponds, reservoirs, irrigation canals and ditches, and marshy borders of lakes and rivers. They don’t live in mountainous areas where cold weather makes their food unobtainable.

Living with wildlife

Muskrats are active throughout the year. Although they may be seen at any time, they are most active at twilight and throughout the night. During the day they may be seen feeding, or basking in the sun when temperatures are low.

Rarely will muskrats be seen very far from water, and they are usually seen swimming. Muskrats tend to swim with their narrow, pointed tails snaking in the water behind them, or arched out of the water.

When startled, muskrats enter the water with a loud splash, and, being strong swimmers, they may swim long distances underwater before surfacing. (They can remain motionless under sparse vegetation, with only their noses and eyes above water, for 20 minutes.)

When cornered or captured, muskrats are aggressive biters and scratchers and can seriously injure pets and humans.

Living Areas

In marshes, ponds, and other water areas east of the Cascade mountains, prominent muskrat lodges are sure indicators of a present muskrat population.

Look for entrances into their bank dens along dams, dikes, and stream banks, particularly west of the mountains. Entry holes are particularly evident where muskrats are living in tidewater areas near the mouths of rivers. When the tide recedes, the entrances are exposed until the tide comes back in.

Similarly, in dry years the water in ponds and reservoirs can drop and expose den entrances. Muskrats will then usually dig new dens farther out in the pond.

Entry holes are 5 to 8 inches in diameter and are located 3 to 36 inches below the surface of the water.

Feeding Areas

Evidence of muskrat feeding includes plants gnawed to a stubble, floating cattail roots or other vegetation that has been clipped, and piles of clipped vegetation under overhanging vegetation or in a well-concealed spot at the water’s edge.

Muskrats sometimes use feeding huts or eating platforms that they create from mud and compacted vegetation. Feeding huts look like small lodges about 1 foot above the water level and are hollow inside; feeding platforms look like small piles of cut vegetation.

Both feeding huts and platforms are built near dens or lodges, and there may be travel channels through the mud leading to them.

Tracks

Muskrat tracks can be found in mud or sand along shorelines. The mark of a dragging tail is sometimes apparent.

Droppings

Muskrat droppings can be found floating in the water, along shorelines, on objects protruding out of the water, and at feeding sites. The animals may repeatedly use these spots, and more than one muskrat may use the same spot. Droppings are dark green, brown, or almost black. They are slightly curved, cylindrical, and about ½ inch long and 3/8 inch in diameter.

Slides

Slides are the narrow trails muskrats make where they enter and leave the water. Slides are about the width of a hand, look like muddy trails, and may be slicked down from the animals’ sliding down them on their bellies.

Preventing conflict

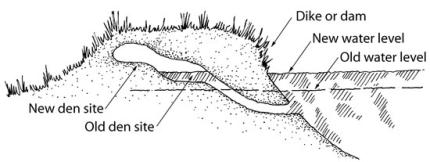

Water-level management: Muskrats (and occasionally voles and Old World rats) dig into dams, dikes, and other embankments to make dens (Fig. 5). Typically these dens have 2 feet or more of earth above them. However, when fluctuating water levels flood their initial den, muskrats burrow farther into the bank or dig new, higher den chambers close to the surface. In such cases this can weaken the bank, or livestock and other large animals can pierce holes in the bank, starting the erosion process.

To prevent muskrats from tunneling higher in an embankment, keep fluctuations in water levels to a minimum. This can require frequently monitoring the spillway to ensure an unobstructed flow, or widening the spillway to carry off surplus water so that it never rises more than 6 inches on the dam.

Water-level manipulation can also be used to force muskrats to other suitable habitat. Raising the water level in the winter to a near-flood level, and keeping it there, will force the animals out of their dens. Similarly, dropping water levels during the summer will expose muskrat dens to predators, forcing them to seek a more secure area.

Slope management: Muskrats prefer to burrow on steep slopes covered with vegetation. Hence, they can be discouraged by keeping side slopes to a 3:1 or less ratio, and by controlling vegetation growth. Managing vegetation by hand can be difficult in large areas, but routine mowing or cutting with a weed whacker can be effective. Only herbicides registered for use next to water should be used, and then only per the manufacture’s recommendations.

If possible, keep livestock off embankments to avoid the chance that an animal will put a hoof through a den chamber. If a roof is pierced, immediately fill in the cavity with soil, rocks, or a mudpack (see below).

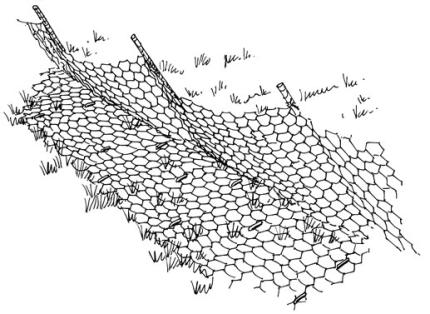

Embankment barriers: A barrier installed 1 foot above to 3 feet below normal water level can prevent muskrats from burrowing into an earth embankment.

A barrier can be made from 1-inch mesh hardware cloth (aluminum and stainless steel are also available), or heavy-duty plastic or fiberglass netting. The barrier should be placed flat against the bank and anchored every few feet along all edges. To extend the life of galvanized hardware cloth, spray it with automobile undercoat paint or other rustproof paint before installation. Since the wire will eventually corrode, do not use this material where people are likely to swim.

Riprapping areas with stone creates an effective barrier and protects slopes from wave action. Stone should be at least 6 inches thick. Do not use rocks larger than 6 inches in diameter because when piled they tend to form cavities, providing hiding places for muskrats and Old World rats.

In situations where muskrats are burrowing into existing rock walls, place gravel or concrete in between the rocks to block up the holes. A permit may be needed when working near state waters (see Legal Status).

Where a burrowing problem is extreme, use a gas-powered trenching machine (available at rental stores) to dig a narrow trench along the length of the embankment. Hand digging will be required to dig to the recommended depth—3 feet below the high-water level. Next, fill the trench with a mudpack. A mudpack is made by adding water to a 90 percent earth and 10 percent cement mixture until it becomes a thick slurry. The resulting solid core will prevent muskrats from digging through the embankment.

Floating dock barriers: Muskrats will burrow into floating docks, generally those floating on Styrofoam, scattering the broken white foam along the shoreline. This becomes an environmental danger, due to birds and other small animal eating this foam. To solve this problem, the dock needs to be pulled up on shore and 1-inch mesh hardware cloth (aluminum and stainless steel are also available) needs to be used to cover the Styrofoam.

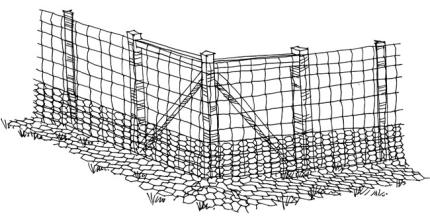

Fences and other barriers: Muskrats are not climbers. A properly designed and maintained 2-foot tall wire fence will prevent muskrats from entering an area. The fence must be taller if snow or other materials are likely to build up near it.

Because muskrats are diggers, the fence will need to extend at least 12 inches below ground. Alternately, a tight fit to the ground and an L extension that runs 24 inches out on the soil surface toward the animal will also prevent entering from underneath and existing fence (Fig. 6).

Welded-wire cylinders around individual plants are often used where only a few plants need to be protected. Note: Lightweight plastic seedling protectors do not work because muskrats can chew through them.

A floppy fence can be constructed as a barrier between an active muskrat colony and a large area needing protection (Fig. 7). To prevent muskrats from walking around the fence, connect each end to an existing, impenetrable solid fence or structure.

Harassment and repellents: Muskrats are wary animals and will try to escape when threatened. When new burrows are discovered early on, the entry holes can be stuffed with rocks, balled-up window screen, and/or rags sprinkled with predator urine (mink, coyote, or bobcat—available from trapper supply outlets and over the Internet) or ammonia. Some people have had success applying used cat litter in this way. Exposing their tunnels from above may also work. The success of this type of control depends on persistence from the harasser and thus is often short-lived.

Large dogs that are awake during the night can be effective at keeping muskrats out of areas.

Commercially available taste repellents may be effective at preventing damage to crops and other plants.

Crop location: Unfenced crops and gardens located close to water will be more attractive to muskrats than those further from water. If you have a choice of where to locate your garden, consider muskrat damage. Natural vegetation buffers next to water bodies can provide feeding areas and reduce the attractiveness of vegetation further from the water.

Lethal Control

Since muskrats are usually found in waterways, there is often an unlimited supply of replacement animals upstream and downstream from where the damage is occurring. Rapid immigration coupled with a high reproductive rate makes ongoing lethal control a “high-effort” method of damage control that is often ineffective. (Lethal control can be effective in areas where the local population of muskrats is still small.) The exclusion methods described and referenced above are often the best long-term solution.

Trapping

Lethal trapping has traditionally been the primary form of control. See Trapping Wildlife and Legal Status or information on trapping muskrats. Note: State wildlife offices do not provide trapping services, but they can provide names of individuals or companies that do.

Shooting

Shooting has been effective in eliminating small isolated groups of muskrats. Shooting muskrats requires good marksmanship. For safety considerations, shooting is generally limited to rural situations and is considered too hazardous in more populated areas, even if legal.

Fumigants

No fumigants are currently registered for muskrat control.

Public Health Concerns

Rabbits, hares, voles, muskrats, and beavers are some of the species that can be infected with the bacterial disease tularemia. Tularemia is fatal to animals and is transmitted to them by ticks, biting flies, and via contaminated water. Animals with this disease may be sluggish, unable to run when disturbed, or appear tame.

Tularemia may be transmitted to humans if they drink contaminated water, eat undercooked, infected meat, or allow an open cut to contact an infected animal. The most common source of tularemia for humans is to be cut or nicked by a knife when skinning or gutting an infected animal. Humans can also get this disease via a tick bite, a biting fly, ingestion of contaminated water, or by inhaling dust from soil contaminated with the bacteria.

A human who contracts tularemia commonly has a high temperature, headache, body ache, nausea, and sweats. A mild case may be confused with the flu and ignored. Humans can be easily treated with antibiotics.

Muskrats are among the few animals that regularly defecate in water, and their droppings (like those of humans and other mammals) can cause a flu like infection, which old-time trappers referred to as “beaver fever.”

Anyone handling a dead or live muskrat or nutria should wear rubber gloves, and wash his or her hands well when finished.

Legal Status

Muskrats are classified as furbearers (WAC 220-400-020). A trapping license is required and they can only be trapped during seasons set by the state.

A property owner or the owner’s immediate family, employee, or tenant may kill or trap muskrats on that property if they are damaging crops or domestic animals ( RCW 77.36.030 ). In such cases, no special trapping permit is necessary for the use of live traps. However, a special trapping permit is required for the use of all traps other than live traps ( RCW 77.15.192 , 77.15.194 ; WAC 220-417-040). There are no exceptions for emergencies and no provisions for verbal approval. All special trapping permit applications must be in writing on a form available from the Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW).

It is unlawful to release a muskrat anywhere within the state, other than on the property where it was legally trapped, without a permit to do so ( RCW 77.15.250 ; WAC 220-450-010).

A permit issued by WDFW is required for work that will use, obstruct, change, or divert the bed or flow of state waters ( RCW 77.55 ). A permit application can be obtained from your WDFW Regional Office or from the Hydraulic Project Approval (HPA) web page.

Because legal status, trapping restrictions, and other information about muskrats change, contact your WDFW Regional Office for updates.