Remember to submit one wing and the tail from your harvested grouse to help monitor these populations. For more information, visit the Forest grouse wing and tail collection page.

Most hunters are aware of three native forest grouse here in Washington, but, according to WDFW biologists, we actually have four. Ruffed grouse are common throughout the foothills and lowlands of Western Washington and forested areas east of the Cascades. The spruce, or Franklin, grouse is found in the lodgepole pine, subalpine fir and Engelmann spruce stands of the Cascades, Olympics and mountains of northeastern Washington. Between the two, elevation-wise, lay the high-country coniferous forest haunts of what we once thought were the two color phases of the blue grouse. Biologists now tell us that the sooty grouse on the west side of the Cascades and the dusky grouse of the eastern slope are actually two distinct species. There is some population overlap, sooties and duskies look very much alike, and from a hunter’s perspective it really doesn’t matter much if they’re all just blue grouse.

All four forest grouse species are native to Washington state, and at least one of the four is found in 34 of our 39 counties. And all four grouse species are exceptionally delicious roasted, seared or slow-cooked!

Washington is also home to white-tailed ptarmigan in high-elevation areas of the Cascade Range, as well as greater sage-grouse and Columbian sharp-tailed grouse in the shrub-steppe of the Columbia Basin. These grouse species are closed to hunting, and sage and sharp-tailed grouse are listed as state endangered species.

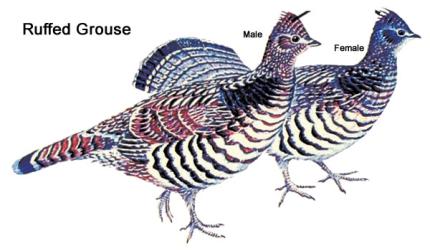

Ruffed grouse

The ruffed grouse is the most widespread of all American upland birds and is hunted throughout the northern United States and southern Canada. Here in the West, it’s found as far south as northern California and central Utah. There are several regional subspecies that range in color from a pale gray-brown to chestnut and dark brown. A color difference is obvious even here in Washington, where birds on the east side of the state tend to show more gray and less brown coloration than west-side grouse. Ruffed grouse are the mid-size model of the upland bird family, measuring 16 to 18 inches in length and weighing from just under to just over a pound.

Ruffed grouse, or native pheasants, as they were once commonly called in Washington, are most abundant in lowland (under 2,000 feet) forests, both coniferous and deciduous, especially those that are a patchwork of clearcuts and standing timber of various ages, intertwined with brushy creek and river bottoms. These areas provide both cover and the berries, seeds, plant and tree buds, clover and other food sources that grouse need. West-side alder bottoms and east-side aspen draws are both good places to look for ruffed grouse, as are timber company lands interlaced with roads of various ages, where grouse can dust and pick gravel. Farm lands that abut forest lands, especially those with old fruit orchards and riparian corridors, also may hold good populations of ruffed grouse.

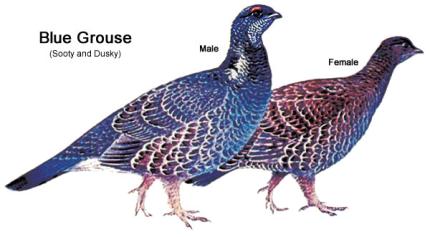

Blue grouse (sooty and dusky)

Blue grouse—both sooty and dusky—are the largest of our grouse, with males measuring more than 20 inches long and weighing as much as a pound a half or more. The body of a male bird ranges in color from a light blue-gray to dark gray, with a yellow-orange comb over each eye. It has several white-based feathers on either side of the neck and has a fairly long, square tail. The smaller hen has a brown back, grayish under parts, and no comb.

The sooty version is typically found in higher elevation (above 2,000 feet) conifer forests of the Olympics and on the western slope of the Cascades, the dusky in similar habitat along the Cascades’ east slope, in north-central and northeastern Washington, and the Blue Mountains.

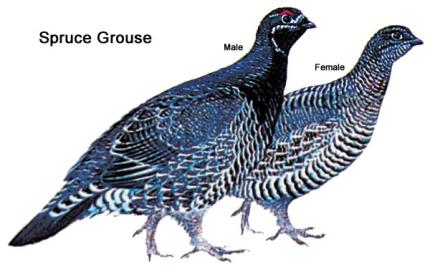

Spruce grouse

Spruce grouse, less abundant and smaller than both blue and ruffed grouse, are found at even higher elevations than the blue grouse, and are somewhat more colorful, though they can be challenging to distinguish from blue grouse depending on age and coloration. Male spruce grouse have a scarlet eye comb over each eye and a black patch that covers the throat and upper breast. The upper portion of the black patch is trimmed in white.

Hunting Strategies

It’s fair to say that the ruffed grouse doesn’t enjoy the kind of celebrity status among Northwest hunters that it gets in New England and the Upper Midwest. It’s the king of upland birds in many states, but just one of many here.

In other parts of the country ruffed grouse are hunted only with shotguns and often with dogs, but Washington hunters are at least as likely to knock it out of a tree with a .223 to the head or pick it off the shoulder of an old logging road with a .22 revolver as they are to take it on the wing with a load of 7 1/2’s from a double-barrel 20-gauge.

Whatever your preferred hunting method or choice of firearms, there are ways to improve your chances of bagging a limit of ruffed grouse.

One way is to spend a lot of time in the woods during the first two or three weeks of Washington’s generous four-month grouse season. Family groups may remain together well into September, and if you locate one bird there’s a good chance the whole gang may be nearby. Finding yourself in the middle of a brood can be a lot like flushing a covey of quail, with birds erupting from the underbrush and flying in every direction.

Early season grouse hunters might do well to concentrate their efforts at higher elevations than they would later in the season. Ruffed grouse often spend their summers feeding and rearing their young farther up the hillsides, then make their way into the lowlands and riparian areas where food and cover may be more plentiful as the weather worsens in late-fall.

Food availability, by the way, may well be a determining factor in whether there are any grouse to be found in a particular area, so knowing where and what they’re eating can very helpful in finding birds. The first thing many veteran grouse hunters do after bagging a bird is open up the crop to see what it’s been eating; that information may lead you to places where you’ll find more birds.

Logging roads, cat trails and fire trails are good places to look for both ruffed grouse and blue grouse. Besides providing a ready source of grit and places for birds to dust, roads and trails allow hunters to cover more ground in less time. And, you may get better shots near the edge of a road than you’ll get farther back in the woods.

Whether hunting open ground or thick cover, a stop-and-go approach often works well on forest grouse, especially ruffs. As you walk, stop briefly every 50 feet or so, or whenever you come to a spot that looks like especially good grouse cover. Scan the area and be ready to shoot when you stop, and stay ready until you’ve taken those first few steps; jittery birds will fly when you stop near them or when you begin to move again.

Ruffed, blue and spruce grouse all have a reputation for not holding very well for a dog, and many Northwest hunters pursue them without a four-legged hunting partner. A pointer or flusher that will stay close, though, will find grouse that a hunter would otherwise pass by, and certainly can be helpful in finding downed birds, especially in heavy cover. The “perfect” dog for this kind hunting might be a pointer that stops short and locks up at the first hint of bird scent, rather than moving in closer and flushing birds out of range (or out of sight behind trees and brush).

If you do hunt typical forest grouse cover with a dog, you might want to do something to make that dog easier to see and/or hear. Many grouse hunters hang a bell on their dogs’ collars to help keep track of their whereabouts and to know when a pointer may have stopped and locked onto a bird. Others add a fluorescent orange vest to increase their dogs’ visibility in the woods. A chest protector can also be helpful for dogs hunting in brushy or wooded areas where scrapes and thorns are common.

Whether flushed by a dog or a human, blue grouse, spruce grouse and, to a slightly lesser degree, ruffed grouse, may chose to fly up and perch in a tree rather than flying away. That tactic can be more than a little frustrating for the purist shotgunner who likes to pick his birds out of the air, but a welcome sight to the hunter toting a rifle or handgun who much prefers a still target.

Even more frustrating for those with a preference for moving birds is that once a grouse finds a comfortable spot in the trees, there’s a good chance it’s going to stay there until you shoot it or run out of ammunition trying. For that reason, some hunters carry two guns into the grouse woods, a shotgun for wing shots and a small-caliber handgun for birds that decide to sit it out.

As it does for big game hunters, an inch or two of fresh snow can be of great benefit to a grouse hunter, especially one who hunts without a dog. Not only are the birds easier to find when you can follow their tracks, but a hunter can move through the woods more quietly and has a better chance of getting close before birds flush.

Hunting in snow, by the way, is just one enticement for hunters to take full advantage of Washington’s long grouse seasons. After most of the deer and elk seasons close in November, forest grouse seem to quickly forget about humans and guns and all the other things that may have made them nervous earlier in the fall. In a word, grouse hunting gets easier. And, if you go after them in December, you’ll likely have the woods to yourself. This late in the season, grouse are typically found near thick, brushy cover or in dense stands of conifer trees, where they seek protection from winter storms and cold temperatures, as well as from predators.

Guns and Ammunition

The “window of opportunity” for a shot at the fast-flying bird in heavy cover can be very small, so many hunters prefer a small, lightweight shotgun for the kind of quick shots they get at ruffed grouse. Although often hard to hit, grouse are usually easy to knock down if you do hit them, so 20-gauges are about as common as the ever-popular 12-gauge among serious grouse hunters.

You don’t get a lot of second shots at a rising ruffed grouse, nor are doubles very common with these rather solitary birds, so a single-shot 20 with a modified choke barrel might work just fine in most situations. There’s something to be said, however, for having as many pellets in the load as possible when you’re shooting at a grouse that’s dodging between trees and zig-zagging around bushes, so a 20-gauge that’s chambered for 3-inch shells isn’t a bad way to go. That 20-gauge you use for ruffed grouse will also work well for spruce grouse, and for blue grouse in most situations, although some hunters like a bigger gun for the bigger birds.

A smaller, lighter gun offers another advantage that may be important to some grouse hunters. Hiking up mountainsides or clawing your way through thick forests in search of grouse is hard work, and your shotgun tends to get heavier with each mile. A few ounces can make a big difference by the end of the day, and a single-barrel 20-gauge is a whole lot lighter than something like a 12-gauge over/under. As in chukar hunting, a shoulder sling may be a worthwhile addition to whatever gun you chose for forest grouse.

As for ammo, more, not bigger is the answer when it comes to shot size for grouse hunting. Some hunters like 6’s, but you get a lot more pellets in the same size load of 7 ½’s, and they’ll knock down a grouse just as well. Some hunters even go as small as size 8 shot, at least for ruffed and spruce grouse. Typical grouse loads range from an ounce to and ounce and a quarter.

Shooting

Perhaps more than any other wing-shooting, knocking ruffed grouse out of the air with a shotgun is a matter of shooting quickly. All forest grouse, but especially ruffs, will startle you when they explode from cover, even when you know it’s coming, and before you can recover, they’ve put 35 yards, a small tree and a couple of tall bushes between themselves and the end of your gun barrel. And that’s if you’re relatively quick to shoulder your gun and start your swing; if you’re slow, you may never see the bird at all.

The term “snap shot” is sometimes used in reference to kind of shot you’ll often take at a ruff. It means that you snap the gun to your shoulder, find a brown (or gray) blur out there among all the vegetation, cover it as best you can with the end of the gun barrel and pull the trigger.

Blue and spruce grouse are often easier targets than ruffed grouse, for several of reasons. In the case of blues, of course, they’re bigger targets, and that helps. You’ll also find both blue and spruce grouse in more open country, where the trees tend to be farther apart and the undergrowth isn’t nearly as thick, usually giving a hunter more time for a decent shot. You may also get a chance to see the bird on the ground before the flush, not only because there’s less cover but because they might live up to their “fool hen” nickname and just sit there looking at you as you approach.

If you fail to shoot a grouse the first time it’s flushed, odds are you’re going to need a bigger load of larger shot should you get a second chance. Like gray partridge, forest grouse, especially ruffed grouse, tend to fly farther and flush at a greater distance with each successive approach. So, if you’re shooting an ounce and a quarter of size 7 ½ lead shot the first time and fail to connect, consider an ounce and three-eighths or even an ounce and a half of 6’s for your second try, should you get one. If it’s an option, choking down a notch or two might also increase your odds for round two.

If your weapon of choice for grouse hunting is a rifle, handgun or bow, of course, you’re not interested in a moving target as much as a still one. It should go without saying that if you’re trying to collect a little camp meat with your deer rifle, you’ll be looking for a head shot, and it’s a very small target. Find a rest of some kind or it’s a tough shot if the bird is any distance away. The good news, though, is that a near miss may be enough to stun him and bring him to the ground. Most of the hunters who shoot their grouse with a .22 also seem to prefer head shots, but others insist that body shots with a small caliber gun don’t really have a big impact on the quality or the quantity of the resultant table fare.