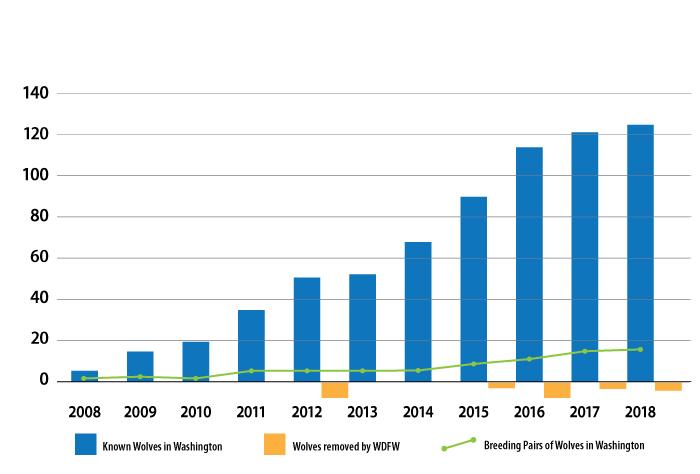

Virtually eliminated from Washington by the 1930s, the state’s gray wolf population has rebounded since 2008, when Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) managers documented a resident pack in Okanogan County. Since then, the state wolf population has grown by an average of 28 percent per year.

WDFW’s annual wolf count in winter of 2018 showed the state has a minimum of 126 individual wolves, 27 packs, and 15 successful breeding pairs – male and female adults who have raised at least two pups that survived through the end of the year.

Results from the count are based on information from partner agencies, aerial surveys, remote cameras, track surveys, ground visual observations, and signals from radio-collared wolves. Contributors to WDFW's annual report include the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Wildlife Services program, the Confederated Colville Tribes, and the Spokane Tribe of Indians. Citizens can help throughout the year by reporting wolf observations.

In 2018, for the first time, WDFW documented the presence of a pack west of the Cascade Crest. A single male wolf in Skagit County, captured in 2017 and fitted with a radio collar, traveled with another wolf through the winter, thereby achieving pack status. That pack was named Diobsud Creek.

A map of all identified packs in the state shows that most occupy land in the Eastern wolf recovery region, which has three times the number of breeding pairs needed to meet recovery goalsThe 2018 survey revealed though that wolf numbers are increasing in Washington's southeast corner and the north-central region.The number of packs in the North Cascades wolf recovery region increased from three to five and the number of successful breeding pairs from one to three.

The 2018 annual report reinforces the profile of wolves as a highly resilient, adaptable species whose members are well-suited to Washington's rugged, expansive landscape. The 2018 survey documented six packs formed in 2018 – Butte Creek, Nason, OPT, Sherman, Diobsud Creek and Nanuem.

State management of wolves is guided by the department's 2011 Wolf Conservation and Management Plan, which establishes standards for wolf-management actions.

Since 1980, gray wolves have been listed under state law as endangered throughout Washington. In the western two-thirds of the state, they are classified as endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act.

WDFW recognizes that public acceptance, as well as collaboration and cohesion with a diversity of stakeholders, is essential for wolf recovery to succeed on a statewide basis. A Wolf Advisory Group (WAG) was created in 2013 to provide a broad range of perspectives to help inform this ongoing management effort. The WAG is tasked with recommending strategies for reducing conflicts with wolves outlined in the state's Wolf Conservation and Management Plan.

An Interagency Wolf Committee was also created to ensure communication and coordination of management approaches to help inform and enhance wolf management efforts in the state. Working together with other state agencies and tribes is imperative if wolf recovery is going to be successful in Washington.

With funding support from state lawmakers, WDFW has also steadily increased its efforts to collaborate with livestock producers, conservation groups, and local residents to minimize conflict between wolves and livestock and other domestic animals.