Providing habitat for songbirds such as finches, sparrows, and nuthatches is a great way to connect with nature wherever you are, including cities and suburbs.

Watching birds visit your space can help you learn about the diversity of species in our state and how they move throughout different areas each year. Birdwatching, either in passing or as a passion, strengthens our connection to nature while also increasing appreciation and understanding of birds and other wildlife.

Birds provide "ecosystem services" such as pest control, seed dispersal, and pollination. The ways you create habitat for songbirds can define the habitat in your area. A mix of bird friendly plants, regularly cleaned feeders, and maintained bird houses can encourage birds to use your yard.

From groundcover to tree canopy, what songbirds need most is healthy habitat. Different species of songbirds use the varying plant layers for different purposes throughout the year. Healthy vegetation can provide the nutritional foods that songbirds need, including fruits, berries, nuts, seeds, and insects. Water features like ponds and birdbaths and nest boxes also support songbirds, however they must be maintained to avoid spreading diseases and parasites.

Creating songbird habitat will also benefit many other wildlife species in your area. To learn how to prepare for wildlife in your area, visit our Living with Wildlife pages for tips to minimize negative interactions between people and wildlife.

How to support songbirds

- Select native plants to provide the best timing, food quality, and shelter for local birds.

- Plant berry-producing plants or colorful wildflowers to attract insects that birds will eat.

- Leave non-hazardous dead standing trees, known as snags, for cavity nesting birds.

- Avoid pesticides. Chemicals can poison birds and the insects they eat, causing declines in songbird populations and ultimately increases in pest insect populations due to less predation.

- Leave grass and brush cuttings out for birds to use as nest materials.

- Provide continually clean water in shallow baths with gradual sloped sides.

- Clean bird baths and water containers to protect birds from disease.

Apply for our wildlife habitat certification program and sign. Our Habitat at Home program is free and open to all wildlife habitat types.

Native plants for songbirds

Native plants are the best way to provide healthy wildlife habitat for songbirds because they provide year-round food through natural production of fruits, berries, nectar, seeds, and nuts while also providing a home for many of the insects songbirds eat. Some birds feed their chicks a diet almost exclusively of caterpillars and other invertebrates.

Native plants are host plants for native insects and encourage a diverse, native insect community. This mix of invertebrates along with seeds and fruits provides songbirds with a nutritional diet. Many plants we find at stores are typically not native species. Although these non-native plants can provide some food and nest material for songbirds, native plants often provide the ideal timing of food and food quality for birds. Your local conservation district may have guidance on where to find native plants for your county.

By providing a variety of native plants in your space, you can provide year-round support for songbirds and the foods they eat. You can focus your plant choices on specific species in your area. The National Audubon Society uses your zip code to provide a list of native plants for your area, detailing what food the plant provides and what birds it supports. Filter by plant type, food produced, or species preferred to narrow your results.

Download the Pacific Northwest trees, Shrubs, Herbs and Perennials and the Birds that Use Them (PDF) guide here.

Songbird diets

| Bird species | Berries and fruits | Invertebrates | Seeds and trees |

|---|---|---|---|

| American goldfinch | Aphids, caterpillars | Asters, birch, chickweed, dandelion, elm, goldenrod, grasses, red alder, red cedar | |

Black-capped chickadee Chestnut-backed chickadees | Blueberry, evergreen huckleberry, serviceberry, thimbleberry | Aphids, caterpillars, flies, leafhoppers, spiders, wasps | Birch, conifers, sunflower, western red cedar |

| Black headed grosbeak Evening grosbeak | Bitter cherry, cascara, chokecherry, manzanita, serviceberry | Bees, beetles, snails, spiders, wasps | Dock, dogwood, fir, juniper, mountain ash, pine, spruce, sunflower, vine maple |

| California quail | Manzanita | Ants, beetles, crickets, grasshoppers | Acorns, catkins, clover, flowers, grain leaves, grass shoots |

| Dark-eyed junco | Ants, beetles, caterpillars, flies, grasshoppers, spiders | Birch, buckwheat, hemlock, juniper, Oregon grape, pine, sorrel, sunflower | |

| Northern flicker | Bayberry, bitter cherry, elderberry | Ants, beetles, butterflies, flies, moths, snails | Dogwood, sunflower |

Nesting

Snags - the wildlife tree

In Washington, about 45 different bird species make their nests in holes in dead or dying trees (called snags). Many of these bird species live in city parks and other human-developed areas. Preserving trees – including dead trees that are not at risk on falling on people or structures – is essential. Putting up nest boxes can also help cavity-nesting birds who provide pest control services by eating insects that damage trees and bushes.

Snags are dead, standing trees in various stages of decomposition. Many birds, mammals, and insects use snags for roosts (shelter) and foraging (food source). With fewer snags across Washington, many cavity-nesting species populations are limited. As lands stewards, it’s important for people to leave as many large snags as we safely can on the lands we care for. Ideally, landscapes would be home to a minimum of three to four snags per acre, or one per residential lot. Visit our Wildlife Tree page to learn how to safely create, maintain, and preserve snags.

Natural nests

Depending on the species, birds build nests from the ground level to tree canopies. Birds use all areas of their natural environment to find a safe space to build their nests, including relatively bare and open areas, tall grasses, shrubs, tops of trees, and more.

Avoid disturbing nesting birds from late winter through spring. Hummingbird nests are especially susceptible to damage, as they are built very early (Anna’s), extremely small, and are well hidden in shrubs and bushes where gardeners easily damage them while doing spring yard work.

During spring yard work, keep an eye out for nests and baby birds. Look for clusters of plant materials, often in the shape of a ball or cup. Listen for frequent and repetitive bird calls as parents will often alert call when people and other animals' approach too closely.

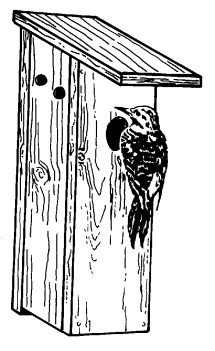

Nest boxes

To select the best bird house for your space, observe birds in your area. Cross-check your list with NestWatch’s list of birds in decline to find a species that is present and in need of habitat help.

Many bird houses for songbirds (PDF) can be built yourself. You can create a nest platform (PDF) that will work for robins, barn swallows, and phoebes. Roost boxes (PDF) are not used for nesting but provide songbirds protection from predators and weather.

Choose or build a nest box for a specific species. The most important part of a bird house is the entrance hole: Too small and your species won’t fit; too big and predators can harm or evict the bird. Non-native or invasive species such as house sparrows, starlings, squirrels, and cats are common harassers of songbird nest boxes.

Materials

Wood is the best material to use for bird houses. It provides insulation and blends into most landscapes. Soft wood such as cedar works for small and large bird houses. If using plywood in your design, make sure it is exterior grade. You can use galvanized nails, but outdoor wood screws will work the best.

Design

Roofs need enough slant to shed water. The top front edge of the roof needs a two-inch (or more) overhang to protect the opening from harsh weather and to keep cats from being able to reach into the box.

Make sure your nest box has a hinged side, bottom, or roof so they can be easily checked and cleaned. Annual cleanings, including the use of a 10% bleach solution, reduce the possibility of spreading parasites and disease.

Bird houses should mimic tree cavities by having rough surfaces on the inside of the box; this gives young birds traction. Make grooves or use a wire brush to make the wood rough on the inside of the box.

All seams that don’t open should be watertight. Caulking the seams with a water-based material works well.

At least two quarter-inch holes should be drilled near the top of the right and left sides of the box, to let air circulate. Small boxes can get very hot. Include a hole in the floor of the house to help drain moisture.

Placement

Most birds select nest sites from late March through May. Most nest boxes should be placed when you begin to see birds arriving. Newly purchased or constructed nest boxes should be set out in the winter to give the houses time to weather and air out.

Nest boxes should be placed in a somewhat concealed area in partial shade where predators cannot get to it. Look to see if birds have a flight path to the entrance hole. A habitat edge—the area where two habitat types meet, such as a forest meeting a meadow—works well for many songbirds. Nest boxes should be firmly attached to a post, tree, or building.

Because most birds are territorial, the average urban yard will likely only hold one nesting pair of many species. This varies species to species and area to area. If you have more land, you have more opportunity for additional boxes and types of boxes.

Protection

Predators pose the greatest threat to birds using nest boxes. Use metal poles to mount your nest boxes or wrap a sheet metal guard around trees or wooden poles to help protect birds from cats and squirrels. Suspending small nest boxes from wires beyond the jumping range of these predators is also effective.

Perches aren't needed. If left on a nest box, perches will attract non-native house sparrows and starlings. Small animals such as mice, native squirrels, bees, and wasps, may also decide to move into a nest box when not in use. If you don't want them there, leave the nest box open to discourage them.

When the nest season is over, leave the nest box open to prevent deer mice from using it as a winter home.

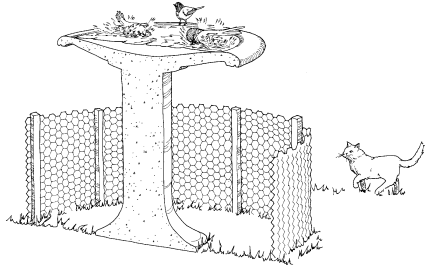

Providing water

Water can turn an average wildlife habitat into an extraordinary one. Some species depend on daily water for drinking, and many birds need water for bathing to keep their feathers fully functional. In the wild, birds get water from moist food sources, snow, dew, rain puddles, ponds, lakes, and streams. However, water can be scarce during summer dry spells and winter freezes. Migratory birds often use backyard birdbaths as they pass through an area.

A birdbath can be anything that holds water; from an upside down frisbee to a landscape pond. Birds will use any size bath if they feel safe as they bathe.

Elements of a birdbath

- Edges that slope gradually, allowing birds to wade into a comfortable depth.

- Shallow water, typically one to three inches at the deepest point. Most birds bathe in water that is no deeper than their legs.

- Bowls with rough texture, so their feet don’t slip.

Types of birdbaths

- Concrete birdbaths feel like stones and have a rough surface birds can easily grip. While heavy, concrete baths are solid and rarely disrupted by adverse weather.

- Plastic birdbaths are lightweight, easily moved, and are easy to clean. However, depending on the design, plastic bowls can be too steep or slippery for birds. Plastic can also crack when water freezes in the winter.

- Ceramic birdbaths are often beautiful to look at, but glazed ceramic can be slippery for birds to move in.

- Hanging birdbaths can be placed in areas where a standing birdbath might be inconvenient, but spilling will be common on windy days.

- Ground-level birdbaths will attract birds and other wildlife. These baths are preferred by ground foraging species such as juncos. They can be larger than the average birdbath but can put birds at risk from outdoor cats and other predators.

Placement

When choosing a spot for birdbaths, consider how you will fill and clean it. To attract a wide variety of birds, place baths in different locations. Birdbaths in shady areas with shrubs or small trees can attract small, shy birds such as warblers and wrens. A bath at ground-level can attract bigger, bolder birds such as juncos.

A small shrub pile within 10 feet of a birdbath will attract birds who rely on accessible shelter, as well as placements near open shrubs and trees with low branches. In areas with a lot of cats, keep at least 10 feet of open space around your baths to avoid ambush opportunities.

Birds are attracted to the sound and movement of water. Built-in fountains, solar bubblers, drippers, and misters help to attract birds and keep water from becoming breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

Don’t worry if the ground around your birdbaths becomes soggy. Barn swallows, robins, phoebes, and hummingbirds will use the mud for nesting material while butterflies will gather there to drink mineral-rich water from mud or wet sand.

Maintenance

Diseases can spread quickly in untended birdbaths. Change water every few days to keep it clean and free of debris. Change water more frequently if many birds are using the same birdbath regularly. Placing birdbaths near hoses or water sources will help you keep up with cleanings more easily.

Scrub small baths a few times each month with a plastic brush to remove algae and bacteria buildup, and more if the water sits stagnant frequently. Even a birdbath that refills automatically must be monitored and cleaned at least once a week, and more often in summer months when use and temperatures are highest. Occasionally disease outbreaks will require bird baths to be emptied or removed for periods of time to discourage birds from congregating and spreading disease. Join or follow a local bird conservation group and WDFW’s e-mail list to know when to stop bird bath use. Part of providing healthy habitat for birds includes being aware of local bird issues and acting responsibly to steward local species.

Birds need to bathe even on the coldest days. While birds can eat snow and ice for hydration, birdbaths will still be used and appreciated by many species. Try to keep bird baths from freezing between dawn and nightfall by adding warmed water or knocking ice apart.

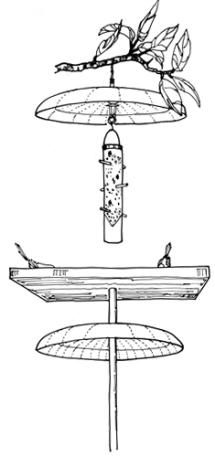

Birdfeeder best practices

Birdfeeders are a great way to observe songbirds up close. People who feed songbirds may have boosted morale and a greater sense of connection to nature. Not to mention, feeding and photographing birds benefits the Washington economy (PDF) through travel expenses and by purchasing feeders, binoculars, camera equipment, etc.

The tips on this page focus on feeding songbirds with seed feeders. For information about feeding hummingbirds, please visit our webpage on creating pollinator habitats. For information on creating songbird habitat that can feed and protect birds year-round, visit our creating songbird habitat webpage.

Considerations before setting up a birdfeeder

Birdfeeders can benefit people and wild birds, but they can also pose challenges to wildlife. By using the recommendations on this webpage, you can feed wild birds responsibly while keeping their health and safety in mind.

There are also ways for you to enjoy backyard wildlife without a birdfeeder! Planting native plants where you live, work, and play provides year-round food and habitat for backyard birds. You can observe more natural hunting, feeding, and other wild bird behaviors in native habitat compared to what you’ll see watching them at a feeder.

Check out this article by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to consider if setting up a birdfeeder is right for you: To Feed or Not to Feed Wild Birds?

In addition to the enjoyment people get from watching birds, birdfeeders can provide supplemental feed to resident and migrating birds. However, they must be cleaned and disinfected regularly to keep them from spreading diseases or making birds sick with old or moldy food.

Birdfeeders can also attract other wildlife you may not want visiting. Backyard birdfeeders are one of the major attractants that bring black bears to peoples’ properties. WDFW encourages limited birdfeeder use through the spring, summer, and fall in most places in Washington, or any time of year where bears are active in your area.

Winter is usually the safest season to put out your birdfeeders because bears are in their dens. Winter is also when birds will be eating the most seeds, so you will likely have more bird visitors this time of year. In summer, songbirds tend to shift their diet to eat more insects, which provide protein to feed their young. For this reason, summer birdfeeders may be less popular with your backyard flock.

Birdfeeder best practices

Quick tips

- Clean seed feeders regularly, about once every two weeks, and more frequently during periods of heavy use or wet weather.

- If you are noticing sick birds at your feeders, or the feeder is attracting unwanted wildlife or pests, consider cleaning and removing your feeders for a couple of weeks to let some wildlife move on.

- Providing one type of seed per feeder will help prevent waste. Consider feeding a variety of seeds in separate feeders to attract multiple species.

- Avoid feeding peanuts in their shells. Discarded peanut shells can attract unwanted wildlife.

- Fill your feeders only with the amount of feed that wild birds will consume promptly. Adding smaller portions of food at a time can help prevent spoilage and attracting unwanted wildlife and pests.

- Feed hulled seeds to prevent waste and make clean-up easier.

- Enjoy observing birds from a distance; do not touch or closely approach them.

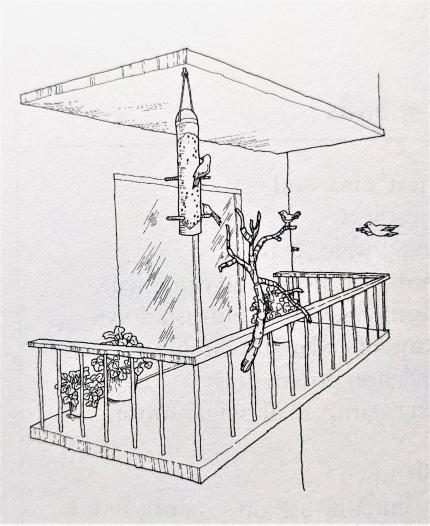

- Be aware that your birdfeeders can attract wild birds towards threats like outdoor cats and windows. Place your feeders in locations where they are less likely to encounter these risks.

Keeping birdfeeders clean

You can prevent disease from spreading at your birdfeeders by keeping them clean. To clean seed feeders, scrub them with soap and hot water, or soak them for 10 minutes with a diluted solution of one part bleach to nine parts cold water before rinsing with warm water. Some feeders are even dishwasher safe. Allow feeders to dry before refilling. Sweep up any discarded seeds or hulls regularly.

Avoid using seed mixes because they can encourage overcrowding and food waste. Mixes are good at attracting birds that enjoy both large and smaller seeds, but unless both types of birds visit your feeder on a regular basis, leftover seeds grow mold and are pushed to the ground. Spilled feed can attract other wildlife like rodents, coyotes, bears, skunks, and racoons, and should be cleaned up every couple of days.

Pro tip: Providing smaller portions of bird food in your feeder at a time can help prevent seeds from spoiling before they’re eaten.

Suet and seeds

If you plan to use suet, only put it out during winter, as it spoils quickly and can melt in the summer.

To offer a variety of seeds, opt for several birdfeeders (PDF) (PDF)that are well-spaced from one another and hold their own type of seed, rather than using fewer feeders with a seed mixture. If using a platform feeder, be sure to clean it daily. These feeders can get particularly messy and pose a greater risk of spreading disease. Using hulled seeds can prevent waste, as hulls will be dropped to the ground when birds are feeding. Start with smaller quantities and add more as needed.

Pro tip: Avoid using peanut feeders. Species that use peanuts typically cache (store) them in hidden locations that sometimes get forgotten or can attract other unwanted wildlife, including rodents. Discarded peanut shells can also be quite messy. Species that prefer peanuts are some of the most resourceful foragers and do not need supplemental feeding.

Location

Not all birds are keen on flying up to birdfeeders. Species such as the dark-eyed junco and spotted towhee prefer to feed on the ground. If you are hoping to attract specific species to your feeder, be sure to research where and what they prefer to eat. Also consider adding perches to your feeding area.

Consider placing your birdfeeder within three feet or at least 30 feet from any windows to prevent window collisions. Placing feeders within three feet of windows prevents birds from gaining enough momentum to seriously hurt themselves, while feeders placed 30 feet or more away from windows prevents the visual confusion that a window can create in a bird’s environment, causing it to strike.

Never place a feeder in spaces where outdoor cats roam. Outdoor cats are excellent hunters and kill billions of birds each year.

Pro tip: Tying some branches to a balcony or adding a small shrub can be a great way to give birds a place to wait their turn at a feeder, preen themselves, or rest.

Resources

Birdwatching basics

Birdwatching, also known as birding, can be done from anywhere in Washington. From national, state, or city parks to yards, neighborhoods, or windows, birdwatching and wildlife viewing offers the opportunity to practice observation and listening skills. With hundreds of resident and migratory bird species in Washington, birding is a perfect and ever-changing activity to do year-round. Many local Audubon chapters offer free bird watching classes and experiences, but plenty of birdwatching can begin at home or be found right in your neighborhood.

WDFW introduction to birding video

Wildlife viewing ethics

When watching birds and other types of wildlife in Washington, be sure to always be respectful of animals, habitats, and other people. People appreciate wildlife in many ways, from hunting and tracking to birding and photography. While you enjoy time outside, be mindful of how your actions may impact others, including wildlife. Give wildlife plenty of space and be inclusive of others when enjoying the outdoors. Wildlife viewing ethics can help guide your interactions while out enjoying Washington’s wildlife.

How to Boost Your Mindfulness and Empathy While Birding(The Audubon Society)

Resources to get started

Learn to identify birds by song to help you spot local Washington species. For a more extensive list, download the Bird Guide App or visit online bird guide to hear hundreds of bird calls and songs. To help you identify birds by sound, we recommend the Merlin App and for keeping lists of birds while birding, we recommend eBird – both of these apps were developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

The National Audubon Society also has many resources to help you explore and learn more.

Threats

Keep cats indoors

Possibly the best thing you can do to help protect wildlife populations is to keep your cat indoors. Additionally, keeping cats indoors not only protects wildlife, it protects cats from being killed by cars, dogs and coyotes, and disease. Indoor cats are safe and healthy cats. Cat attacks kill 2.4 billion birds in the U.S. alone. When providing habitat for songbirds and inviting or attracting them into your spaces, it is important to create a safe space for birds to feed, bathe, and raise young free from cat predation.

If you need help transitioning a cat (PDF) to an enriched indoor life PAWS’ Safe Cats, Healthy Habitat program has many resources available. Catios (PDF) are a great way to protect both cats and the wildlife in your area.

Domestic and feral cats make up almost 50% of bird injuries and deaths at local rehabilitation centers. Due to the bacteria found in cat saliva, even animals not immediately killed by cats often die soon after. If the bird you find has been attacked by a cat and has open wounds, contact your local wildlife rehabilitation center.

Prevent window strikes

Bird-building collisions are one of the leading cause of bird deaths in urban areas. Up to one billion birds die each year from window collisions. Birds can’t see clear glass, and reflective glass surfaces often mirror the sky and nearby vegetation, tricking birds into thinking it is a safe area.

- Put markers on the outside of windows to make them visible to birds. You can use decals or opaque dots to help birds see the surface.

- Hang strings or cables, or use outside screens in front of windows.

- Draw patterns on the glass using tempura paints.

- Instead of using clear glass in all your windows, choose frosted, etched, or glass blocks in areas with high bird activity.

Hang birdfeeders to avoid collisions

Hanging bird feeders can be the best option to protect birds from cats and other predators. However, be sure to place them where birds will be safest from window collisions. Generally, feeders that are between three and 30 feet away from windows pose the greatest threat of bird collisions, so feeders that attach directly to a window can be a good solution.

Ensure the place you pick provides quick access to vegetation so birds can find safe shelter. Additionally, choose a spot that does not have easy access for cats and other predators from ledges or nearby branches. For more on bird feeders, review the Bird feeders best practices section above.

You can create your own window decals to help songbirds avoid window strikes.

Window strike injuries

If a bird hits your window and is still alive, gently place it in a small cardboard box with crumpled tissue on the bottom. Make sure the top of the box is secure and that the box has proper ventilation. Find a safe, quiet spot away from noise, people, and animals and limit human and pet exposure as much as you can. Then, contact your local wildlife rehabilitation center.

Found an injured or orphaned bird?

Do not attempt to treat or raise a wild animal yourself – not only is it illegal, but wildlife rehabilitation requires specialty training and expertise. Wildlife species differ widely in terms of their capture, care, and handling requirements. Without this expertise, you could make an animal’s situation worse or kill it. If kept improperly, animals may lose their natural fear of humans and become more vulnerable to predation or injury. Euthanasia is often the only option for wild animals that become habituated to humans. Learn more about helping injured wildlife on our blog.

Nestlings and fledglings

Young birds leave the nest before they are fully ready to fly. If the bird on the ground has full but fluffy feathers, it is most likely a fledgling, meaning it has left the nest but is still being fed and cared for by its parents. Leave the bird where it is if possible and avoid that area while the bird is cared for. Unless injured, a fledgling bird should be left where it is. You can help by keeping cats, dogs, and curious children away from the bird so the mother can continue to feed it. Removing a native bird from its environment is illegal and deprives it of the essential care it needs from its parents.

If you find a baby bird with sparse feathers or none at all, it is a nestling that has likely fallen or been pushed from a nearby nest. You can give the bird a helping hand by returning it to the nest, if you can find it. It’s best to wear gloves for your own protection. Local songbirds have a limited sense of smell, and parents will continue to care for their young even if they’ve been touched by a human.

If you can’t find the nest or accessing it is too dangerous, put the baby bird where its parents can find it and where it will be safe from cats. Use a small plastic berry basket, margarine tub, or similar container lined with shredded paper towels (cotton products tend to tangle up in birds’ feet). With a nail or wire, fasten the makeshift nest to a shady spot in a tree or tall shrub near where the bird was found. Next, place the nestling inside, tucking the feet underneath the body.

The parents will usually come back in a short time and will feed the babies in the container just as if it were the original nest. Often, you will see the mother going back and forth between each “nest,” feeding both sets of babies. You can use this chart created by PAWS (PDF) to decide how to help a baby bird.

If a bird is injured, contact your local wildlife rehabilitation center. Do not give the bird water or food unless expressly directed to by a rehabilitation specialist.