The marine shoreline is a vibrant ecosystem found in Western Washington. From the Pacific coast to the Puget Sound, this ecosystem supports a wide range of fish and wildlife. The dynamic nature of marine shorelines and the interactions between water and land is what makes this ecosystem so rich and filled with life.

Marine shorelines also support a large part of our state’s economy and provide vital recreational, spiritual, and other essential quality of life benefits. The Washington State Department of Natural Resources' short film, "The Nearshore", illustrates the complexity of the marine shoreline ecosystem and why it is home to many important habitats and species.

Description and range

Physical description

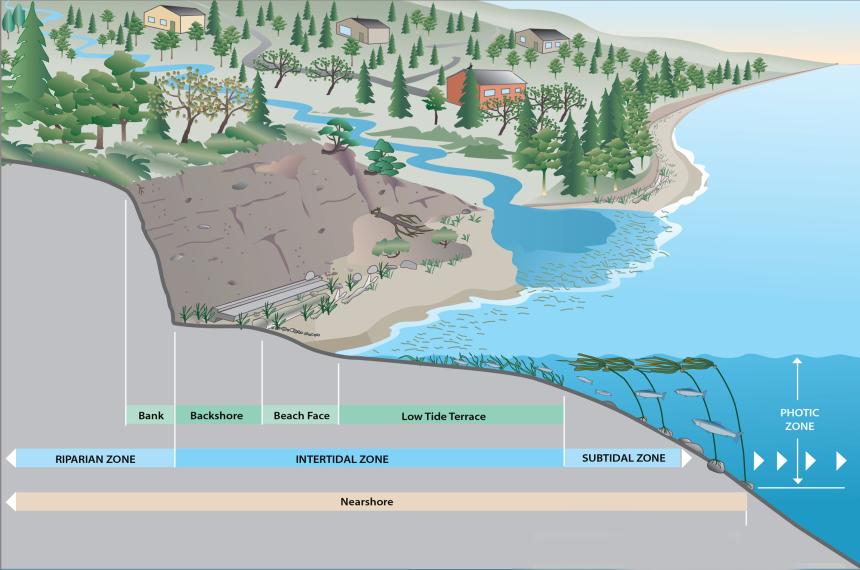

Marine shorelines, together with estuaries, encompass what is known as the nearshore. The nearshore ranges from the deepest saltwater areas along shorelines where the sun can still reach underwater vegetation, all the way up to the top of coastal bluffs and rocky cliffs that line beaches. The nearshore also extends upstream to the highest part of the river that is influenced by the tide.

The variety of physical habitats adds richness to ecological communities, which in turn sustain human communities along the coast.

The nearshore can be divided into four zones:

- Riparian zone: Marine-influenced uplands that may have vegetation (trees, shrubs, grasses) as well as rocky cliffs and banks that may include “feeder” bluffs whose sediment feeds and sustains beaches.

- Intertidal zone: Area directly influenced by tidal changes in water levels throughout the day, ranging from the high tide level to the low tide level. This zone is biologically among the richest of coastal habitats, and includes beaches, estuaries, and large river deltas.

- Subtidal zone: Area that is permanently underwater. Rocky bottoms in the subtidal zone are particularly important for eelgrass, native oyster reefs, and forage fish.

- Photic zone: Uppermost layer of marine shore waters where phytoplankton gets sufficient sunlight to perform photosynthesis, which in turn, enriches this area with nutrients.

There are a variety of physical features within the nearshore formed by different material types (sand, rock, mud) interacting with a variety of hydrologic processes (waves, tides, river flow).

Physical features of the nearshore include:

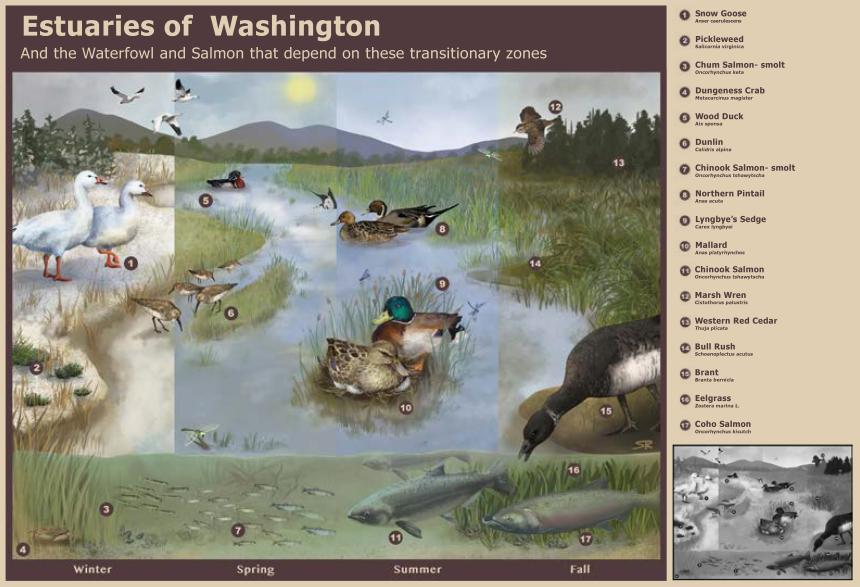

- Estuaries: Bodies of water where freshwater of rivers meets saltwater of the ocean or Puget Sound, creating an environment that is a mixture of saltwater and freshwater.

- Salt and brackish marshes: Wetlands mostly confined to the intertidal portions of estuaries, coastal lagoons and bays, and behind sand spits or other areas protected from waves. Specific habitats can vary based on salt content, frequency of tidal flooding, and types of soil.

- Intertidal mudflats: Formed by tides and rivers depositing sediment in nearshore environments.

- Eelgrass beds: Underwater vegetated areas in intertidal and subtidal zones that create 3D habitat in an otherwise flat setting. Eelgrass slows water currents, dampens waves, and traps sediments.

- Sand dunes: Created when the ocean current deposits sand as the current weakens. Dune systems also include vegetated areas behind the beach, known as beach strand.

Physical features of the nearshore environment are constantly changing. They vary over short and long-time scales, with daily tides, seasonal shifts in ocean currents, and flooding and low flow of rivers. Human activities also affect the nearshore environment, but it is hard to distinguish human-related changes to naturally occurring changes. Human activities that commonly affect the nearshore include installing dikes to drain estuaries for urban development and agriculture as well as installing shoreline armor such as bulkheads to prevent erosion on coastal properties.

Geographic range

Pacific coast and Lower Columbia River

Washington’s Pacific coast spans over 155 miles from Cape Flattery to the Columbia River. The northern shoreline from Cape Flattery south to Point Grenville has long sections of rugged, rocky cliffs, high wave energy, and high species diversity. This rocky habitat gradually merges with more gravel and sand beaches. The southern coast from Point Grenville south to the Columbia River has long stretches of sand beaches and includes Washington’s three largest coastal estuaries: Grays Harbor, Willapa Bay, and the Lower Columbia River. The Columbia River is so big that the tidal zone travels 146 miles upstream from the Pacific Ocean to the Bonneville Dam; the saltwater influence extends about 30 miles.

Puget Sound

Puget Sound has approximately 2,500 miles of shoreline. Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia form an inland sea called the Salish Sea that connects to the Pacific Ocean through the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

The modern shoreline of Puget Sound developed as global sea-level rise began slowing during the last 5,000 to 6,000 years. Rivers have continued to deliver sediment to the coast, building large estuarine deltas at their mouths. Streams have carried sediment from small coastal watersheds to the shore, contributing to the gradual evolution of small estuaries.

Wave action has eroded the coastline and transported sediment, which formed beaches and led to the evolution of a wide variety of coastal landforms. Pacific Ocean waves and swell have little influence on Puget Sound except near the entrance, so wave generation is directly linked to local wind conditions.

Species

Washington’s nearshore encompasses a variety of unique habitats, supporting important ecological communities. Many marine mammals, raptors, waterfowl, shorebirds, fish, and invertebrates depend on the nearshore for all or part of their life cycle. This richness in biodiversity makes the nearshore environment a statewide conservation priority in Washington.

Plants

Distributed along Washington’s coastline, rock cliffs and steep bluffs may be unvegetated or sparsely vegetated with grasslands, meadows, and shrubs.

Sand dunes host native trees, shrubs, and grass species such as dunegrass and red fescue. Rare species include pink sand verbena which was thought to be extinct until 2006 when a population was found at the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge.

Non-native plants can take over vegetated dunes. European beach grass, which was widely planted to stabilize beaches, has spread extensively for over 125 years. American beach grass, a native species to eastern North America, has spread throughout the Long Beach Peninsula. These plants have altered natural beach formation and dune processes, changing the composition of native plants.

Across salt and brackish marshes and tidal flats, some native plant species are primarily found in branched channels that drain these areas. Marshes typically have plants that are rooted beneath the surface with vegetation that emerges from the water. Marsh vegetation is influenced by the tides and saltiness of the water. Characteristic plant species include seashore salt grass, sea milkwort, jaumea, pickleweed, sea blight, and arrow grass.

Intertidal mudflats usually have sparse, saltwater aquatic vegetation. In intertidal and subtidal zones, channels may be unvegetated or lined with eelgrass (Zostera marina). Eelgrass forms patchy beds with roots that stabilize sediments in interlocking, dense mats. Eelgrass beds cover thousands of acres in the flats of Willapa Bay, Grays Harbor, and Padilla Bay estuaries.

Spartina, an invasive plant, has become established in estuaries, raising tidal elevations, displacing eelgrass and native marsh plants, and reducing habitat for migratory waterfowl, invertebrates, and possibly fish.

Fish and wildlife

In nearshore areas, seabirds, peregrine falcons, and belted kingfishers use cliffs and soils above the reach of waves as nesting sites. At the base of cliffs, harbor seals use wave-carved platforms above sea level as pupping sites where they rear their young, and fur seals use rocky habitats as temporary haul out sites. Killer whales (orcas) lurk near these shorelines, preying on seals and other marine mammals. Areas offshore are used by cormorants, scoters, harlequin ducks, and pigeon guillemot as foraging sites. At high tide, many fish species look for food on rocky shores.

Beaches and sand dunes

Unique sand‐loving, rocky‐shore organisms are found where rocky shores give way to long stretches of sandy beach and rock cliffs. Dunes and adjacent fine sand beaches provide roosting and foraging habitat for shorebirds such as sanderlings as well as nesting habitat for snowy plover. Drift logs are used as feeding perches and resting places for eagles and falcons and as windbreaks for roosting shorebirds. Dune shrubs and larger trees provide habitat for perching birds. Various small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians find cover among vegetation and logs. Many invertebrates use dune habitat, including rare butterflies such as Taylor’s checkerspot and Island marble.

Small schooling fish such as surf smelt and Pacific sand lance spawn on beaches. They are collectively known as “forage fish” and are an important food source for salmon and other fish, marine birds, and marine mammals. Pacific herring, anchovies, and sardines are also forage fish.

Estuaries

Near stream mouths in coastal areas and estuaries, juvenile salmon acclimate to their changing environment as they migrate from a freshwater stream to the open ocean. Salmon are an anadromous fish, which means they are born in freshwater, spend most of their lives in saltwater, and return to freshwater to spawn. Nine anadromous salmonid species are found in Washington: Chinook, chum, pink, coho, and sockeye salmon; steelhead, sea-run coastal cutthroat trout, Dolly Varden, and bull trout. Lampreys are another type of anadromous fish that can be found in estuaries. These eel-shaped, parasitic fish use their sucker-like mouth to cling onto and feed off their host fish.

In estuaries, tiny non-native New Zealand mudsnail feed on algae, sediment, plant and animal detritus – all of which would otherwise be consumed by native snails and insects. These invasive snails were first discovered in the Lower Columbia River estuary in 2002 and populations are rising.

Salt marshes and intertidal mudflats

Salt and brackish marshes and intertidal mudflats are important habitats used by insect larvae, amphipods (shrimp-like animals), polychaetes (marine worms), snails, and other invertebrates. These species are prey for numerous fish and wildlife, including waterfowl, shorebirds, herons, raccoons, otter, mink, salmon, and steelhead. In sandy or muddy areas, these invertebrates, as well as algae, depend on the structure of eelgrass beds. Brant geese eat eelgrass – an important food source during their twice‐annual migration on the Pacific Flyway. Commercially important species such as Dungeness crab and red rock crab, Pacific herring, salmonids, shrimp, and flatfishes all rely on eelgrass beds at some point in their life cycles.

In coastal and estuarine habitats, non-native European green crab prey on shore crab, clams, and small oysters. First found in Washington in 1998, sightings of this invasive crab have increased since 2016, particularly in Puget Sound.

Species of Greatest Conservation Need

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (PDF) include species that are state listed as sensitive, threatened, or endangered, or federally listed as threatened or endangered, as well as additional species thought to need conservation attention. These species of greatest conservation need are the basis for the State Wildlife Action Plan, which is an effort to protect rare species while keeping common species common.

The plan links species of greatest conservation need to the specific habitats they depend on. To not only survive but thrive, these species require quality habitats.

The following list features Species of Greatest Conservation Need that depend on marine shoreline habitats.

Birds

- Common loon*

- Dusky Canada goose

- Harlequin duck

- Marbled godwit

- Marbled murrelet*

- Peregrine falcon

- Red knot

- Rock sandpiper

- Streaked horned lark*

- Surf scoter

- Western grebe

- Western high Arctic brant

- Western snowy plover*

- White-winged scoter

Fish

- Broadnose sevengill shark

- Bull trout*

- Chinook salmon* (Puget Sound, Lower Columbia River)

- Chum salmon* (Columbia River, Hood Canal-summer)

- Copper rockfish

- Eulachon smelt* (Southern)

- Pacific herring (Georgia Basin)

- Pacific sand lance

- Surf smelt

- White Sturgeon (Columbia River)

Invertebrates

- Island marble butterfly*

- Olympia oyster

- Oregon silverspot butterfly*

- Pinto abalone*

- Sand verbena moth

- Siuslaw sand tiger beetle

- Straits acmon blue butterfly

- Taylor's checkerspot butterfly*

Mammals

- Destruction Island shrew

- Killer whale (orca)*

* Indicates "at-risk" species, meaning the animal is state listed as sensitive, threatened, or endangered, or is federally listed as threatened or endangered.

At-risk fish

"At-risk" species include fish that are state listed as sensitive, threatened, or endangered or federally listed as threatened and endangered. The following section highlights at-risk species that rely on marine shoreline habitats at some point during their lives.

Bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus)

Bull trout are federally threatened. The species is native to the Pacific Northwest. Bull trout are a char and members of the salmonid family. They are closely related to Dolly Varden trout, lake trout, and brook trout, and have distinctive light spots on a dark background. In Western Washington, the migrating (anadromous) form of bull trout is found in coastal estuaries and marine waters. These populations eat small saltwater fish such as sand lance, surf smelt, and herring. They return to their natal streams to spawn, primarily in small stream headwaters. Resident (non-anadromous) fish may spend their entire lives in small streams, or some may migrate from small streams to larger rivers and back again to spawn, while others may migrate into lakes or reservoirs, then go back to spawn in their natal stream or river. In the Puget Sound and Pacific coast, bull trout inhabit estuaries and nearshore marine waters for up to five months each year, possibly returning to these waters every year for up to 10 years.

Did you know?

- Their large head and mouth give bull trout their name. Unlike trout and salmon, they do not have teeth in the roof of their mouth.

- The Coastal-Puget Sound population contains the only anadromous (sea-run) forms of bull trout in the lower 48 states.

- Bull trout are highly mobile, sometimes visiting multiple streams and rivers each year.

Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

In Washington, there are two federally threatened Chinook salmon stocks (Puget Sound, Lower Columbia River) that depend on marine shoreline habitats. Most Chinook spawn in large rivers such as the Columbia and Skagit but may use smaller streams with sufficient water flow. Some Chinook travel hundreds of miles upstream to their spawning grounds. These fish enter streams early and comprise the spring and summer runs. Fall runs spawn closer to the ocean, often using small coastal streams. Chinook fry (baby salmon) rear in freshwater for up to a year. Juvenile salmon (smolts) leave the freshwater of streams and spend time in estuaries, where they undergo physical changes enabling them to tolerate saltwater when they migrate to the sea.

Did you know?

- Chinook, nicknamed “king” or “tyee” salmon, are the largest Pacific salmon and can grow to more than 100 pounds.

- Because of their larger size, they can spawn in larger gravel than most other salmon.

- In the ocean, Chinook are largely piscivorous (fish eaters) and grow to maturity for one to six years before migrating back to natal rivers to spawn.

Learn more about Chinook salmon.

Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta)

In Washington, there are two federally threatened chum stocks (Columbia River, Hood Canal-summer). Chum salmon use small coastal streams and the lower reaches of larger rivers. They often use the same streams as coho salmon, but coho tend to move further up the watershed and chum generally spawn closer to saltwater. This may be due to the chum’s larger size, which requires deeper water to swim in, or their jumping ability, which is inferior to coho. Chum fry (baby salmon) do not rear in freshwater for more than a few days. Shortly after they emerge, chum fry swim downstream to the estuary and rear there for up to several months before heading out to the open ocean.

Did you know?

- During spawning, adult males develop large teeth resembling a canine’s, which may explain this species’ nickname “dog salmon.”

- Chum weigh from 10 to 33 pounds.

- Washington state is about as far south as chum salmon travel.

Eulachon smelt (Thaleichthys pacificus)

The southern stock of eulachon is federally threatened. This stock extends from Mad River in northern California north to British Columbia. In Washington, they occur in the lower Columbia River and its tributaries below Bonneville Dam, several Pacific coastal river systems, and the Elwha River.

Eulachon are a migrating (anadromous) smelt. Adults and juveniles spend most of their lives in the ocean, returning after two to five years to estuaries or freshwater rivers to spawn. Like salmon, adult eulachon die after spawning. Their eggs attach to, and grow in, coarse sand layers. After hatching, larvae immediately wash downstream. In estuaries, larval fish grow into juveniles in two to three weeks before moving to nearshore marine waters.

Did you know?

- Eulachon have many other names—smelt, hooligan, oolichan, fathom fish, and candle fish.

- They are called “candle fish” because spawning eulachon are so rich in oil, they can be dried, strung on a wick, and burned as a candle.

- Eulachon were historically an important food staple and valuable trade item of indigenous communities.

At-risk wildlife

"At-risk" species include animals that are state listed as sensitive, threatened, or endangered or federally listed as threatened and endangered. The following section highlights at-risk species that rely on marine shoreline habitats at some point during their lives.

Killer whale (Orcinus orca)

Three populations of killer whales, known as the Southern Residents, transients, and offshores regularly occur in Washington. The Southern Residents are listed as a federally endangered species, and all three populations are state endangered.

The Southern Resident population feeds primarily on Chinook salmon, chum salmon to a lesser extent, and occasionally other fish. Transient killer whales feed on seals and other marine mammals along shorelines. Offshore animals primarily feed on sharks and other fish. The decreased availability of Chinook salmon has limited the Southern Resident population’s productivity. The health of killer whales is impacted by high levels of chemical contaminants, noise and disturbance from vessels and other human activities, as well as large oil spills.

Did you know?

- Killer whales are the largest member of the dolphin family, weighing up to 11 tons and measuring up to 32 feet long.

- Females outlive males, living up to 90 years in the wild.

- Most killer whales live in pods (highly social groups of maternally-related individuals) and hunt their prey as a team.

Learn more about killer whales.

Island marble butterfly (Euchloe ausonides)

The Island marble is a rare butterfly, believed to be restricted to two San Juan Islands. In 2020, this species became federally listed as endangered. Thought to be extinct since 1908, the butterfly was re-discovered by biologists during a prairie survey in San Juan Island National Historical Park in 1998. It was also found a few years later on Lopez Island but has not been seen since 2006. The entire population exists on the south end of San Juan Island.

The island marble inhabits open grasslands, disturbed sites, and herbaceous or sparsely vegetated habitats such as native prairie, pastures, sand dunes, gravel pits, and marine beaches where their annual host plants grow.

Did you know?

- After emerging from its chrysalis stage, adult females will mate, lay their eggs on mustard species flowers (host plants), and then die.

- After hatching, caterpillars (larvae) of this species eat mustard flowers and seed pods before leaving their host plant.

- This species spends about 300 days of its year-long life as a chrysalis waiting for the right environmental cues to undergo metamorphosis and emerge as a butterfly.

Learn more about Island marble butterfly.

Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha taylori)

Taylor’s checkerspot is federally and state listed as endangered. It is a Pacific Northwest native (endemic) butterfly. It was historically found in open prairie and grassland habitats from southeastern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, south through the Puget Sound region of Western Washington, and into the southern Willamette Valley of Oregon. In addition to prairies, it also occupies coastal bluffs and dunes as well as small forest openings. The species is currently restricted to a scattering of eight populations in Washington, one population in British Columbia, and two populations in Oregon.

The decline of this butterfly has accompanied the loss of its habitats. Since 2006, habitat enhancement for Taylor's checkerspot has become a focus of conservation efforts. Continued effort is greatly needed to reconnect this butterfly’s fragmented and isolated habitat.

Did you know?

- In spring, females lay eggs on specific plants that serve as food for the emerging caterpillars (larvae).

- Caterpillars enter a suspended state of development (diapause) from early summer to late winter.

- Local zoos and the Sustainability in Prisons Project have been instrumental in breeding caterpillars for release at suitable sites to help with species recovery.

Learn more about Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly.

Oregon silverspot butterfly (Argynnis zerene hippolyta)

The Oregon silverspot butterfly is federally and state listed as endangered. This butterfly is likely no longer in Washington and will require reintroduction from captive reared or wild populations in Oregon. In Washington, historically the Oregon silverspot butterfly inhabited sites along the coast from Westport to the Columbia River. WDFW has led habitat restoration efforts on coastal sites in Pacific County to prepare for future butterfly reintroductions. The butterfly uses open, short-stature grasslands in coastal dunes, bluffs, and nearby forest glades.

Did you know?

- Adult butterflies emerge from chrysalis stage in early-to-late summer with males emerging first.

- Adults only lay their eggs on their preferred host plant: violets (genus Viola).

- The caterpillars (larvae) secrete a chemical that protects them from predators.

Learn more about Oregon silverspot butterfly.

Pinto abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana)

Pinto abalone are state endangered. These large marine snails range from Baja California, Mexico to Alaska. They are the only abalone species found in Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska.

Abalone exist in groups and use rocky reef habitat. Pinto abalone in Washington are generally found between water depths of nine to 60 feet. They are grazers, feeding on diatoms and kelp, living on bedrock or boulder reefs. The abalone's preferred habitats and location in relatively shallow water makes them particularly vulnerable to harvest. Pinto abalone populations in Washington face threats from changing ocean conditions, illegal harvest, reduced genetic diversity, disease, contaminants, and native or introduced predators.

Did you know?

- This snail is the first marine invertebrate to be state listed as endangered in Washington.

- An adult is about the size of a softball and has the feel and consistency of a human tongue.

- They are important for rocky reef habitat, grazing on algae and diatoms, clearing rocky areas for kelp and other organisms.

Learn more about pinto abalone.

Common loon (Gavia immer)

The common loon is state listed as sensitive. This species has a small breeding population in Washington, mainly in northern remote areas. They migrate annually between saltwater (Salish Sea and outer coast) and freshwater, returning to the same inland breeding lakes each year.

Due to the loon’s life history and its small population, loons are highly vulnerable to increased development and recreational activities at nesting lakes. These lakes need to be actively monitored and managed to prevent further loss of nesting loons.

Did you know?

- Common loons typically do not mate until at least six years of age.

- While great for diving, common loon’s legs are located so far back on their body that they cannot walk on land.

- The adult loon’s laughing “tremolo” call is actually a distress signal to its mate. Learn about and listen to different loon calls.

Marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus)

The marbled murrelet is federally listed as threatened and state listed as endangered. Its population in Washington is low and declining.

The murrelet inhabits the nearshore marine environment in western North America near nesting habitat. It is most abundant in northern Puget Sound and the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and least abundant along the southwestern Washington coast. Because of its preference to breed in mature and old growth forest, their populations have been severely affected by loss of this habitat. Availability of food resources in the marine environment, such as Pacific anchovy, Pacific herring, eulachon, and Pacific sand lance, may also influence population status.

Did you know?

- Marbled murrelets nest in mature and old growth forest up to 60 miles inland from marine waters and fly back and forth to feed fish to their young.

- Breeding murrelets do not build nests but use tree “platforms” instead, such as a large branch with moss or witches’ broom deformity.

- Juvenile murrelets fly directly from their forest nest to marine waters without the aid of their parents.

Learn more about marbled murrelet.

Streaked horned lark (Eremophila alpestris strigata)

Streaked horned larks are federally listed as threatened and state listed as endangered. They are found on prairie habitat south of Puget Sound, coastal beaches, and dredge spoil islands along the lower Columbia River. Primary concerns for this species are habitat loss and degradation as well as human-activities such as mowing grass at breeding sites.

This subspecies of horned lark is a focus of WDFW’s conservation efforts with partners such as Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Center for Natural Lands Management, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, civilian airports, Oregon State University, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, American Bird Conservancy, Port of Portland, and The Evergreen State College.

Did you know?

- The “horns” on the lark’s head are actually tufts of feathers.

- The streaked horned lark occasionally breeds on airport grasslands.

- Horned lark chicks are mostly independent at four weeks old.

Learn more about streaked horned lark.

Western snowy plover (Charadrius nivosus)

The western snowy plover is federally listed as threatened and state listed as endangered. Washington's snowy plover population is very small and vulnerable to a variety of impacts, such as predators, adverse weather, shoreline modification, dune stabilization, and recreational activities.

In Washington, snowy plovers are found (in any season) on coastal beaches, sand spits, dune-backed beaches, and sparsely vegetated dunes. These birds forage on a variety of invertebrates found at coastal intertidal areas and around the margins of lagoons and salt marshes.

Did you know?

- Snowy plovers nest in shallow depressions on sparsely-vegetated, flat, open beaches and sand spits above the high tide line.

- To distract and lure predators away from their nests and chicks, snowy plovers pretend to have a broken wing.

- Snowy plover parents do not feed their chicks; shortly after hatching, chicks forage for their own food, usually small insects.

Places to explore

Washington’s wildlife areas provide habitat for fish and wildlife as well as land for outdoor recreation. Each year, thousands of people visit these areas to hunt, camp, hike, fish, and enjoy other outdoor activities. These activities support local economies and contribute to Washington’s wildlife-related recreation industry.

WDFW owns or manages nearly a million acres of land on 33 wildlife areas across the state. In addition to wildlife areas, WDFW also owns or manages hundreds of water access areas that provide boating or fishing access to lakes, rivers, and marine areas.

All visitors to WDFW lands need to display a current Discover Pass or WDFW Vehicle Access Pass. Annual and daily Discover Passes are available online at fishhunt.dfw.wa.gov or at license vendors across the state. Vehicle Access Passes are free with the purchase of most Washington hunting or fishing licenses.

Wildlife area unit

- Chimacum Wildlife Area Unit

The Chimacum Unit provides beach and estuary access and maintained trails that connect to county park trails. Habitat types include conifer and deciduous riparian forest, and estuary.This unit is managed for restoration and protection of stream, riparian, and estuarine habitat on Chimacum Creek.

- Chinook Wildlife Area Unit

The Chinook Unit, near the mouth of the Columbia River, provides diverse recreational opportunities. Waterfowl, elk, and deer are hunted during established seasons; this unit is a pheasant release area. This site also offers an excellent opportunity for bird watching. The management focus of this property is estuary restoration. Fields are managed to provide elk winter forage and also to benefit waterfowl.

- Nooksack Wildlife Area Unit

The Nooksack Unit of Whatcom Wildlife Area extends from the Nooksack River estuary north to WDFW's Tennant Lake Unit. Together these units protect the eastern bank of the Nooksack River from its mouth to Ferndale, as well as most of Tennant and Silver creeks. Native riparian vegetation and tidally influenced habitats are under restoration for salmon and waterfowl, and approximately 100 acres of corn is planted annually with 10 percent of the crop left standing as winter waterfowl forage. A 1.5 mile, dike-top trail offers walking opportunities along the Nooksack River.

- Oyhut Wildlife Area Unit

The Oyhut Unit is on the south end of the Ocean Shores peninsula in Grays Harbor County. This unit is popular for waterfowl hunting and birding. It is one of four remaining nesting sites in the state for the western snowy plover — a state listed endangered and federally listed threatened species. The unit is maintained as waterfowl habitat and for associated recreational opportunities.

- Skagit Headquarters Wildlife Area Unit

The Skagit Headquarters Unit — also known as Wiley Slough — is tidal marsh (estuary) on Fir Island, west of and adjacent to Freshwater Slough. The unit is predominantly vegetated by cattail and sedge and used extensively by waterfowl and other waterbirds, shorebirds, raptors, and passerines.

- North Willapa Bay Wildlife Area Unit

The North Willapa Bay Unit is made of multiple properties that are primarily managed for the conservation of critical estuarine and coastal wetland habitats. Protecting and restoring these habitats benefit salmon, waterfowl, shorebirds, marine invertebrates, and other fish and wildlife species. The Smith Creek and North River properties include estuarine and riparian habitats. At the Potter Slough property, dike removal restored hundreds of acres of tidelands. Recreation opportunities on the unit include hunting, fishing, boating, and wildlife viewing.

- Spencer Island Wildlife Area Unit

The Spencer Island Unit is a flat, grassy intertidal complex ringed by mixed forest, located in the Snohomish River estuary. This unit offers waterfowl hunting, hiking, and wildlife viewing opportunities. A 1-mile, elevated trail is a special feature. The island is jointly-owned/managed by WDFW and the Snohomish County Parks and Recreation Department. In 2005, an act of nature breached a dike on the WDFW property on the northwest side of the island, restoring tidal influence to the area. WDFW and its partners are working together to continue restoration of the estuarine system.

- Union River Wildlife Area Unit

The Union River Unit at the inland terminus of Hood Canal, which is part of a larger complex of conservation and recreation lands that encompass Lynch Cove, the mouth of the Union River, and surrounding forested shorelines. The unit is managed for multiple uses, including birdwatching, nature study, waterfowl hunting, and estuary habitat restoration. This unit also features an interpretive trail.

State Parks

- Cape Disappointment State Park

Cape Disappointment is a 2,023-acre camping park on the Long Beach peninsula, fronted by the Pacific Ocean and looking into the mouth of the Columbia River. Walk through old-growth forest or around freshwater lakes, saltwater marshes, and ocean tidelands. Launch your boat from Baker Bay. Benson Beach is a popular clam-digging destination, and fishers love to set up on the North Jetty to catch salmon and crab.

- Fort Worden Historical State Park

Fort Worden Historical State Park is a 432-acre multi-use park on the northeast coast of the Olympic Peninsula. The park has more than 2 miles of saltwater shoreline and a variety of services and facilities. Visit the aquarium and museum at the Port Townsend Marine Science Center which is an educational and scientific organization devoted to understanding and conserving our marine and shoreline environment.

- Grayland Beach State Park

Grayland Beach State Park is a 581-acre, year-round, marine camping park with 7,449 feet of spectacular ocean frontage, just south of the town of Grayland. The park attracts kite flyers, observers, and people wanting a day at the beach. The wide sandy beach goes for miles, as surf sounds mingle with the honks and squawks of shore and sea birds. The park offers campsites and yurts within walking distance of the ocean.

- Joseph Whidbey State Park

Joseph Whidbey State Park is a 206-acre day-use park with 3,100 feet of saltwater shoreline on the Strait of Juan de Fuca in northern Puget Sound. Its west-facing views from Whidbey Island include Victoria, B.C., Lopez Island, and the strait. A grand beach and an excellent trail system through wetlands, forests, and fields make this day-use park a destination on any visit to Whidbey Island.

- Scenic Beach State Park

Scenic Beach State Park is a 121-acre camping park with 1,500 feet of saltwater beachfront on Hood Canal. The park is known for its wild, native rhododendrons that bloom in spring. This picturesque little park, with its views of Mount Olympus hovering over the Olympic Mountains, welcomes everyone.

- Saltwater State Park

Saltwater State Park is a 137-acre camping park featuring 1,445 feet of saltwater shoreline on Puget Sound, between Tacoma and Seattle. Wade in the shallows, make sandcastles, or play on the driftwood-strewn shore. Explore Saltwater's tide pools or its seasonal salmon spawning in McSorley Creek. If you prefer to view sea life from under the water, Saltwater is the only state park with an underwater artificial reef for diving.

Other places to visit

- Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge

This refuge encompasses the Nisqually River Delta, a biologically rich and diverse area at the southern end of Puget Sound. Here, the freshwater of the Nisqually River combines with the saltwater of Puget Sound to form an estuary rich in nutrients and detritus, supporting a web of sea life. Also, learn about the nearshore at the Nisqually Reach Nature Center at the nearby WDFW Nisqually Unit.

- Cherry Point Aquatic Reserve

This reserve is a unique aquatic ecosystem located in the Strait of Georgia on the western shores of Whatcom County, Washington. Designated in 2010, the reserve protects unique habitat that supports marine and intertidal species that are crucial to the health of the Salish Sea. Watch the 3-minute video A Look at Cherry Point Aquatic Reserve to learn more.

- Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge

The graceful arch of Dungeness Spit protects nutrient-rich tideflats for migrating shorebirds in spring and fall; a quiet bay with calm waters for wintering waterfowl; an isolated beach for harbor seals and their pups; and abundant eelgrass beds for young salmon and steelhead nurseries. Open to the public year-round--hiking, wildlife viewing, and photography are popular activities.

- Olympic National Park Beaches

Kalaloch and Ruby Beach are located on the southwest coast of the Olympic Peninsula. Kalaloch is a great place for bird watching. Western gulls, bald eagles, and other coastal birds can be spotted nesting and feeding along the southern coast. Beach 4 in the park is an excellent location to search tidepools for sea stars, and anemones of various colors at low tides.

- Padilla Bay National Estuary Research Reserve

This reserve protects an 8,000-acre eelgrass bed, one of the largest in the contiguous United States. Located in the northern reaches of greater Puget Sound, at the saltwater edge of the Skagit River delta in the Salish Sea, the reserve is eight miles long and three miles across, and attracts tourists, artists, nature enthusiasts, birdwatchers, hunters, and fishermen.

- Willapa National Wildlife Refuge

This refuge is comprised of diverse ecosystems including salt marsh, muddy tidelands, forest, freshwater wetlands, streams, grasslands, coastal dunes and beaches. This rich mix of habitats provide places for over 200 bird species to rest, nest and winter, including waterfowl (ducks and geese) and shorebirds. Many other animals, including chum salmon, Roosevelt elk, and over a dozen species of amphibians also benefit from the protection of the refuge.

Conservation

Marine shorelines are identified as a “Priority habitat” under the Priority Habitat and Species Program. Priority habitats are habitat types or elements with unique or significant value to a diversity of species.

A priority habitat may consist of:

- A unique vegetation type such as shrubsteppe or a dominant plant species such as juniper savanna;

- A described successional stage such as old-growth forest; or

- A specific habitat feature such as cliffs.

The Department has identified three priority habitats in the nearshore environment for conservation and management:

- Relatively undisturbed nearshore estuaries of Washington’s outer coast including Grays Harbor, Willapa Bay, and the mouth of the Columbia River.

- Relatively undisturbed non-estuarine nearshore of Washington’s outer coast.

- Relatively undisturbed nearshore of Puget Sound, including the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Admiralty Inlet, the San Juan Islands, and Hood Canal.

WDFW management tools

The Priority Habitat and Species Program is the Department's primary means of transferring fish and wildlife information from our resource experts to local governments, landowners, and others who work to protect habitat. This information is used primarily by cities and counties to implement and update land use plans and development regulations under the the Growth Management Act and Shoreline Management Act.

In the Department’s State Wildlife Action Plan “Habitats of Greatest Conservation Need (PDF)” chapter, marine shorelines include two ecological systems of concern: (1) Temperate Pacific Tidal Salt/Brackish Marsh, and (2) North Pacific Maritime Coastal Sand Dune and Strand.

The State Wildlife Action Plan is part of a nationwide effort by all 50 states and five U.S. territories to develop conservation action plans for fish, wildlife, and their natural habitats—identifying opportunities for species’ recovery before they are imperiled and more limited. A habitat of greatest conservation need is defined as an ecological system and community types that are essential to the conservation of Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Washington.

Conservation threats and actions needed

Climate change, invasive plant and animal species, such as spartina and European green crab, coastal development, overharvesting (fish and shellfish species), and degraded water quality are all stressors that threaten marine shoreline habitats.

Marine shoreline habitats are impacted by common land use practices. Discharge from municipal, industrial, and agricultural practices degrades the physical and chemical conditions of these habitats. The pollutants emitted by these sources have harmful impacts throughout marine food webs, especially for species at the top of the food chain such as Southern Resident killer whales.

One of the main causes of marine shoreline habitat loss over the last 150 years has been urban, residential, and agricultural development. Shoreline armoring occurs over 27% of Puget Sound, protecting homes, businesses, and other infrastructure from shoreline erosion. In addition, approximately 70-80% of historic estuary habitat has been lost to diking, drainage, and filling. Many of Puget Sound’s largest cities, such as Seattle, Tacoma, and Everett, are located on filled estuary. In the Lower Columbia, there has been a 70% loss of vegetated tidal wetlands and 55% of forested uplands due to development.

Threats resulting from habitat loss include declining prey resources; for example, less forage fish for seabirds and fewer Chinook salmon for Southern Resident killer whales.

Sea level rise is the most significant climate change stressor for salt and brackish marshes. As the sea level rises, tidal salt marshes will be completely submerged causing declines in vegetation unless they migrate inwards through sediment accumulation. Nearshore and estuary systems will also be affected by sea level rise, as well as impacts from increased wave action and higher water temperatures. Oceanic ecosystems are at risk from ocean acidification, which is already impacting oysters and other shellfish in Puget Sound.

Major threats to marine shoreline habitats

- Agricultural side effects

- Alteration of hydrology

- Climate change, ocean acidification, and sea level rise

- Dams and diversions

- Habitat loss and degradation

- Invasive species

- Recreation impacts

- Roads and development such as shoreline armoring (e.g., bulkheads)

Actions needed to maintain quality marine shoreline habitats

- Agricultural management

- Habitat conservation and protection, including actions to minimize risk of oil spills

- Invasive species control

- Land use planning requirements to protect habitat

- Private land incentives

- Restoration of estuaries and shorelines

- Water management to maintain or re-configure water sources and routes

Learn more about threats to marine shorelines and the actions needed to protect them in WDFW’s State Wildlife Action Plan, Chapter 4: Habitats of Greatest Conservation Need (PDF).

Conservation efforts

WDFW works to restore, conserve, and protect habitat throughout the Washington’s marine shoreline ecosystem through a variety of programs and partnerships. From leading projects on the Department’s lands to providing incentives for shoreline landowners, WDFW provides technical expertise, project assistance, and funding opportunities to support and restore marine shoreline habitats. These are a few of our programs focused on marine shoreline conservation and restoration.

- Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project

This project is a long-term effort to identify significant ecosystem problems in the Puget Sound nearshore, evaluate potential solutions, and restore and preserve habitat. - Estuary and Salmon Restoration Program

The Estuary and Salmon Restoration Program provides funding and technical assistance for nearshore restoration and protection efforts in Puget Sound. - Shore Friendly Grant Program

Shore Friendly is a brand developed to encourage forgoing or removing shoreline armor, incentivizing landowners and communities to inspire behavior change. - Puget Sound Habitat Strategic Initiative

The Habitat Strategic Initiative, co-led by WDFW and the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, facilitates and empowers strategic, collaborative recovery of Puget Sound. - Columbia River restoration

WDFW’s Lower Columbia Estuary team reconnects floodplains to the mainstem Columbia River and restores tidal processes by working with landowners to find solutions for improving salmon and other native fish access to rearing habitat.

Restoration efforts

WDFW is dedicated to protecting and restoring all nearshore habitat and environmental processes that are important to the species of greatest concern. Below are a few projects we are doing with our partners to restore marine shoreline habitat.

Leque Island Restoration Project

Leque Island, located between Port Susan and Skagit bays, was once entirely salt marsh. In the late 1800s, early non-indigenous people built dikes around the perimeter of the island to convert the area to farmland and homesteads. The Leque Island Unit is part of the Skagit Wildlife Area. WDFW began acquiring properties on Leque Island in 1974, and now manages the entire island. With the help of Ducks Unlimited, WDFW removed 2.4 miles of levee on the Leque Island Unit to restore 250 acres of tidal marsh habitat in the Stillaguamish River watershed. This habitat is used by juvenile Chinook salmon as they transition from fresh to saltwater, as well as shorebirds, waterfowl, and many other species. Because Puget Sound's Southern Resident killer whales rely upon Chinook salmon for food, the project also closely aligns with orca recovery efforts.

Learn more about the Leque Island project.

Duckabush Estuary Restoration project

WDFW, in partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Hood Canal Salmon Enhancement Group, is proposing a restoration project on the Duckabush River estuary in Jefferson County. The project would occur mostly on public land at the Duckabush Wildlife Area Unit managed by WDFW.

The project would reconnect the Duckabush River to neighboring floodplains and wetlands by modifying local roads and elevating Highway 101 onto a bridge spanning the area where freshwater from the Duckabush River meets saltwater of Hood Canal.

The Duckabush River estuary is currently impacted by fill, dikes, and road infrastructure, which blocks water channels and limits critical habitat for fish and wildlife, including endangered salmon species.

Learn more about the Duckabush Estuary Restoration project.

Chinook Estuary Restoration

In Baker Bay, near the mouth of the Columbia River Estuary, WDFW manages 1,000 acres of the 1,500-acre Chinook estuary as part of the Johns River Wildlife Area. After upgrading the tide gates in 2007, WDFW has worked with local landowners to manage them for optimal fish passage while still protecting private properties from flooding. Currently, the tide gates are partially open most of the winter and closed completely only when king tides and large storm events coincide. The goal is to have the tide gates completely raised by March, when juvenile salmon begin to use the habitat.

WDFW expanded estuary restoration efforts by acquiring an additional 200 acres of land. A natural tidal channel and historic wetlands were restored by removing old farm road crossings and filling drainage ditches. WDFW continues to enhance the estuary habitat by planting native species, preserving historic estuary lands, and working with the community to find more flexibility with tide gate management.

Get involved

Volunteer

- Register as a WDFW volunteer to help with activities that benefit fish, wildlife, and habitat.

- Volunteer with a Land Trust – find your local land trust.

- Volunteer with the National Park Service – participate in a coastal cleanup.

- Join a Volunteer Advisory Committee to participate in the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office’s grant programs that protect marine shoreline ecosystems.

Get involved in your community

- If you’re a landowner along the marine shoreline of Puget Sound, check out the Shore Friendly Program to learn how you can protect your property and the Puget Sound.

- Learn about estuaries and marine shorelines with Puget Sound Estuarium or Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership.

- Get involved with your local Conservation District – find your conservation district.

- Provide input to your local government about development in marine shorelines areas and the impacts to fish and wildlife species. For example: Take advantage of public engagement opportunities afforded through Washington State’s land use planning frameworks, including the Growth Management Act. All towns, cities, and counties are required to protect critical areas, which include fish and wildlife habitat conservation areas.

- Contact a regional fisheries enhancement group to learn about volunteer opportunities near you such as planting parties, vegetation monitoring and maintenance at restoration sites, and educational outreach at community events.

- Help your county’s Marine Resources Committee promote marine resource stewardship.

- Help track plant and wildlife activity on marine shorelines. Use iNaturalist to share your observations and help scientists see how native species are thriving.

- Learn about managing invasive species through the Washington Invasive Species Council.

- Get involved with the Voluntary Stewardship Program if you are an agricultural landowner, producer, or other agricultural operator, and your county participates.

- Reach out to your local habitat biologist or private lands biologist (PDF) for ideas on how to conserve, protect, and restore marine shorelines in your area.

Support public lands

- Buy a Discover Pass for yourself or as a gift. This parking pass provides access to recreation lands managed by WDFW, Washington State Parks, and Washington Department of Natural Resources; and purchasing the pass provides funding to those agencies.

- Recreate responsibly in the great outdoors, including following “Leave No Trace” principles.

Share your marine shorelines experience

- Share your photos and observations of marine shoreline wildlife species to help us monitor wildlife populations and habitat.

Resources

Wild Washington lesson plans

WDFW publications and guides

- Marine Shoreline Design Guidelines

This publication was created to inform responsible management of Puget Sound shores for the benefit of landowners and our shared natural resources.

- Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project technical reports

Technical reports are all peer reviewed publications for use by others to support restoration in Puget Sound and beyond.

- Puget Sound Maps

Web accessible mapping resources of the Puget Sound nearshore.

- 2021 Nearshore Restoration Summit and Synthesis

Recorded presentations from a variety of experts focused on Puget Sound beaches, deltas, and embayments.

- State of the Washington Coast: Ecology, Management, and Research Priorities

This report describes the physical habitats and ecological communities of Washington’s Pacific coast.

- Small overwater structures: a review of effects on Puget Sound habitat and salm…

This scientific review examines available literature on impacts of small, private docks and piers (small overwater structures) on nearshore environments and salmon. Learn more about research and partnership opportunities.

Educational materials

- Department of Ecology Puget Sound estuary curriculum guide

Teacher guides that can be downloaded for three grade levels. They are intended to complement a visit to Padilla Bay but are also adaptable to other locations, especially the Pacific Northwest.

- Shore Friendly Program video series

This video series explores beach formation, shoreline erosion management, and the big picture of marine ecosystems. The Shore Friendly Program provides resources for shoreline landowners to maintain and protect their investment while also protecting fish and wildlife that need healthy nearshore habitats to thrive.

- Wild Washington Program

Wild Washington lessons incorporate disciplines ranging from math and science to art and literature. Lessons align with the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction’s state and national environmental and sustainability learning standards. Lessons related to marine shorelines include Coastal Ecosystems of Washington, Hungry Orcas, Declining Salmon, Aquatic Invasive Species, and more.

- At-home educational resources

Activity ideas focused on threats Washington’s wildlife face and the ways you can help by being a good steward for wildlife, habitat, and the environment. Activity themes include Ecosystems in Washington, Protecting our oceans, Be a good steward, and more.

- Salmon viewing locations

A map of areas to view salmon migrating and/or spawning.

Other resources

- Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership

The Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership is a nonprofit, a National Estuary Program, and a collection of dedicated scientists, educators, and community members who are passionate about the Columbia River. The partnership focuses on the lower 146 miles of the Columbia River, from Bonneville Dam to the Pacific Ocean, including the tidally influenced portions of tributaries in that area. The watershed includes 28 cities, nine counties, and 45 school districts within Oregon and Washington.

- Washington Coast Restoration and Resiliency Initiative

The Coast Salmon Partnership guides the long-term protection and restoration of Washington Coast’s salmon and steelhead populations in some of their last, best habitats in the contiguous United States. The grant program is aimed at proactively addressing the region’s highest priority restoration and resiliency needs and putting people to work restoring coastal lands and waters.